Archived Content

The National Institute of Mental Health archives materials that are over 4 years old and no longer being updated. The content on this page is provided for historical reference purposes only and may not reflect current knowledge or information.

Depression’s Flip Side Shares its Circuitry

• Science Update

Humans tend to be overly optimistic about the future, sometimes underestimating risks and making unrealistic plans, notes NIMH grantee Elizabeth Phelps, Ph.D., New York University. Yet "a moderate optimistic illusion" appears to be essential for maintaining motivation and good mental health.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Phelps and her colleagues have now shown that such "optimism bias" may be rooted in the same brain circuitry as depression, which is marked by a tendency to be overly pessimistic.

The same circuitry was also in play when this normal bias toward positive thinking was temporarily turned off by depriving the brain of the mood-regulating chemical messenger serotonin, in another recent fMRI study by NIMH intramural research psychiatrist Wayne Drevets, M.D., and colleagues.

Through this circuit, the anterior cingulate, just behind the front of the brain, regulates the amygdala, an emotion hub deep in the brain.

Phelps and colleagues reported their findings in the October 24, 2007 issue of Nature.

They set out to discover why, for example, people tend to expect to live longer than average, underestimate their chances of getting a divorce and overestimate their likelihood of successful careers.

Fifteen healthy volunteers were scanned while they were remembering or imagining future events – like "winning an award" and "the end of a romantic relationship" – to see how their brain activity related to their ratings of these experiences and their scores on standard scales of optimism.

True to form, the participants rated future positive events as more vivid and expected them sooner than negative ones.

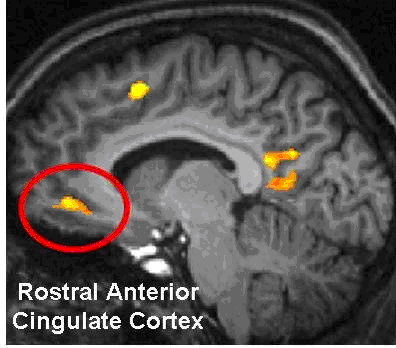

The cingulate/amygdala circuit showed more activity and connectivity with optimistic than with negative imaginings. The higher an individual scored on rating scales of optimism, the more an area at the front of the cingulate (see graphic below) activated. This rostral anterior cingulate appears to be the seat of these judgments, where emotional, motivational and autobiographical information is weighed – with an eye for the positive.

But the same circuit has a flip side. Citing an earlier study by Drevets and colleagues, Phelps's team pointed out that this cingulate/amygdala circuit may also underlie the pessimism and impaired imagining seen in depression.

In the recent study by Drs. Drevets, Jonathan Roiser, and colleagues, healthy volunteers who had never been depressed lost their optimism bias and showed brain activity changes in similar regions to Phelps and colleagues when they lacked tryptophan, the precursor chemical that the body uses to make the chemical messenger serotonin.

This first fMRI study to document neural and behavioral responses to emotionally-charged words when the healthy brain is starved of serotonin was published online September 19, 2007 in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Researchers had previously shown that people with a history of depression experience mood symptoms following such serotonin depletion, along with alterations in emotion-regulating brain circuits.

In the current study, 20 healthy participants initially made significantly more inappropriate responses to positive words while performing a task that required them to respond only to negative words, indicating that their attention was grabbed by the positive words – the optimism bias. However, after they took capsules containing essential amino acids, minus tryptophan, depriving their brains of serotonin, this normal bias toward positive words disappeared.

fMRI scans revealed that this loss of focus on the positive was accompanied by decreased cingulate activity in response to positive stimuli, particularly in a region toward the back of the cingulate cortex that was also implicated in the Phelps study. Drevets and colleagues have proposed that by taking the breaks off the amygdala, such decreased cingulate activity may play a role in depression.

By helping to accentuate the positive, serotonin, which is enhanced by antidepressants, may provide resilience in the face of life's hard knocks, suggest the researchers.

An area at the top front of the cingulate (yellow area in red circle) activated more when subjects imagined positive than negative future events. Activation was especially strong in subjects who scored high on scales of optimism. The researchers propose that this rostral anterior cingulate cortex weighs emotional, motivational and autobiographical information with an eye for the positive. Evidence suggests that decreased anterior cingulate regulation of the amygdala and other emotion hubs deep in the brain may be at the root of depression.

Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA . Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007 Oct 24; [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 17960136

Roiser JP, Levy J, Fromm SJ, Wang H, Hasler G, Sahakian BJ, Drevets WC . The Effect of Acute Tryptophan Depletion on the Neural Correlates of Emotional Processing in Healthy Volunteers.Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 Sep 19; [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 17882232