Multimedia

Health Topics

-

Director's Innovation Speaker Series: Youth Suicidal Behaviors: Where Do We Go From Here

Director's Innovation Speaker Series: Youth Suicidal Behaviors: Where Do We Go From Here

-

Lilly Kelemen, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

Lilly Kelemen, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

-

Community Conversations Webinar Series Video: Is Your Kid Often Angry, Cranky, Irritable?

Community Conversations Webinar Series Video: Is Your Kid Often Angry, Cranky, Irritable?

-

Webinar: Timely and Adaptive Strategies to Optimize Suicide Prevention Interventions

Webinar: Timely and Adaptive Strategies to Optimize Suicide Prevention Interventions

Populations

-

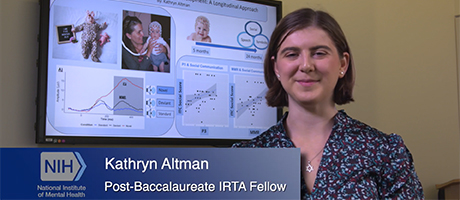

Kathryn Altman, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

Kathryn Altman, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

-

Director’s Innovation Speaker Series Video: Youth-Centered Approaches to Media Research

Director’s Innovation Speaker Series Video: Youth-Centered Approaches to Media Research

-

Episode 1: Jane the Brain and the Stress Mess

Episode 1: Jane the Brain and the Stress Mess

-

Episode 3: Jane the Brain and the Upset Reset

Episode 3: Jane the Brain and the Upset Reset

Research

-

Director's Innovation Speaker Series: Youth Suicidal Behaviors: Where Do We Go From Here

Director's Innovation Speaker Series: Youth Suicidal Behaviors: Where Do We Go From Here

-

Lilly Kelemen, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

Lilly Kelemen, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

-

Ifeoma Azinge, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

Ifeoma Azinge, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

-

Kathryn Altman, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition

Kathryn Altman, Winner of the 2024 NIMH Three-Minute Talks Competition