Archived Content

The National Institute of Mental Health archives materials that are over 4 years old and no longer being updated. The content on this page is provided for historical reference purposes only and may not reflect current knowledge or information.

Depression’s “Transcriptional Signatures” Differ in Men vs. Women

Divergent illness processes may point to sex-specific treatments

• Science Update

Brain gene expression associated with depression differed markedly between men and women in a study by NIMH-funded researchers. Such divergent “transcriptional signatures” may signal divergent underlying illness processes that may require sex-specific treatments, they suggest. Experiments in chronically-stressed male and female mice that developed depression-like behaviors largely confirmed the human findings.

NIMH grantee Eric Nestler, M.D., Ph.D., of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and colleagues, reported their findings online August 21, 2017 in the journal Nature Medicine.

Discovering the likely differing causes of “depression” may lead to more precise diagnosis and treatment. Sex differences could hold clues. Women are 2-3 times more likely than men to develop depression. Evidence has been mounting of sex differences in symptoms, treatment responsiveness and brain changes associated with the disorder. But, until now, little was known about molecular mechanisms in specific brain regions that might underlie such differences.

To explore these, Nestler’s team sequenced the transcriptomes of six suspect brain regions in postmortem brains of 13 males and 13 females who had depression and 22 unaffected people.

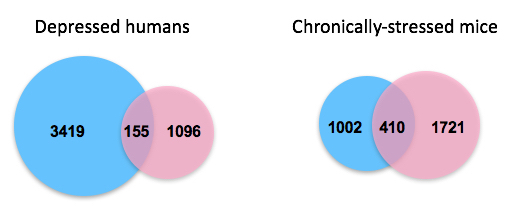

In both sexes, all six regions showed illness-linked changes in transcription, when compared to brains of controls. But there was little overlap (5-10 percent) between male and female brains in depression-linked gene expression patterns across the regions. Upon further analysis, males showed only 31 percent of illness-linked modules of co-expressed genes seen in females, and females shared only 26 percent of such modules with males. Moreover, functions of the depression-associated modules largely differed between the sexes. The transcriptional changes affected several brain cell types in males, but mostly neurons in females. Yet, despite the lack of overlap at the level of gene transcripts, several of the same overall molecular pathways were ultimately implicated in depression in both men and women.

Similarly, genetically identical male and female mice showed little (20-25 percent) overlap in transcriptional signatures associated with depression-like behaviors experimentally induced by chronic stress. In the brain’s executive hub and reward center, expression of dozens of the same implicated genes increased and decreased in the same sex-specific directions in both humans and mice. This indicated that both species may share sex-specific stress-induced pathology, converging on several of the same biological pathways.

“The mouse work allows investigation into the cellular mechanisms by which the observed changes in gene expression lead to changes in neural circuit function and behavior,” explained Laurie Nadler, Ph.D., chief of the NIMH Neuropharmacology Program, which co-funded the study.

Using genetic engineering, the researchers uncovered molecular mechanisms underlying the sex-specific effects of changes in activity of two genes never previously linked to depression or stress responses.

The study results suggest that depression-related stress susceptibility is mediated by mostly different genes and partly different pathways across the sexes, although these converge in some common outputs. Since genome-wide studies have not turned up sex differences in genetic variation (DNA) associated with depression, the researchers suggest that the differences instead take place at the level of gene transcription. Such changes in similar gene modules organized and expressed differently across brain regions in males and females may disrupt coordinated neural activity needed to cope with stress, they propose.

”These findings illustrate the importance of examining sex differences in neuropsychiatric phenomena,” said Dr. Nestler. “They also provide insight into possible approaches for the treatment of depression that selectively target women or men.”

changes in postmortem prefrontal cortex (an executive decision-making

hub) of depressed men (blue) compared to those found in depressed

women (pink). They found more, but still limited, overlap between gene

expression changes in the comparable brain region of chronically stressed

male and female mice. They say the latter finding is particularly striking,

given that the mice were genetically identical, exposed to identical

stresses, and subsequently showed equivalent depression-related

behavioral abnormalities. The study suggests that depression appears to

involve fundamentally different molecular abnormalities in men versus women.

Source: Eric Nestler, M.D., Ph.D., Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Reference

Sex-specific transcriptional signatures in human depression. Labonté B, Engmann O, Purushothaman I, Menard C, Wang J, Tan C, Scarpa JR, Moy G, Loh YE, Cahill M, Lorsch ZS, Hamilton PJ, Calipari ES, Hodes GE, Issler O, Kronman H, Pfau M, Obradovic ALJ, Dong Y, Neve RL, Russo S, Kazarskis A, Tamminga C, Mechawar N, Turecki G, Zhang B, Shen L, Nestler EJ. Nat Med. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1038/nm.4386. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 28825715

Grants

MH096890, MH051399