Archived Content

The National Institute of Mental Health archives materials that are over 4 years old and no longer being updated. The content on this page is provided for historical reference purposes only and may not reflect current knowledge or information.

NIMH Grantee Wins One of Science’s Most Coveted Prizes

Deisseroth honored for optogenetics, CLARITY, depression circuitry insights

• Science Update

Dr. Karl Deisseroth discusses “Optical tools for discovery in neuroscience” at a meeting of NIH BRAIN Initiative researchers (drag slider to 20:40). Deisseroth served on the initial working group that designed the NIH’s BRAIN Initiative.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grantee Karl Deisseroth, M.D., Ph.D., of Stanford University, has been awarded one of science’s most generous prizes. A German foundation presented the inventor of technologies that are transforming neuroscience with its 4 million euros Fresenius Prize on May 31, 2017. In bestowing the honor, the Else Kroner Fresenius Foundation cited his development of optogenetics, hydrogel-tissue techniques, such as CLARITY, and “circuit-level insight into depression” – all made possible by NIMH grants to Deisseroth since 2004.

“NIMH funding afforded Deisseroth and his team the freedom to take risks – and these bets have paid off,” explained NIMH director Joshua Gordon, M.D., Ph.D. “Their pioneering development of multiple innovative methods incorporating quantitative disciplines, particularly engineering, have, in just the past decade, changed the way thousands of neuroscientists study brain circuitry every day. Their focus on developing such new tools is widely credited with inspiring the NIH BRAIN Initiative .”

In an essay accompanying the Prize announcement, Deisseroth notes that the main discoveries for which he is being honored “were neither part of disease-related research, nor even constrained in terms of specific applications to basic science.” He implores scientists to “communicate to the broader public that any specific goal of a research portfolio – be it disease treatment or national interest – is best served with a major basic research component, where direct links between research and goal are not known, or even knowable.”

The Foundation awards the Fresenius Prize every 4 years, each time in a different area of biomedical science. This year’s competition focused on mid-career scientists exploring the “biological basis of psychiatric diseases.” The winner personally receives 5 million euros, with 3.5 million earmarked for the lab’s future research.

Deisseroth, a psychiatrist who regularly sees patients – as well as a neuroscientist – says in an interview published in conjunction with the Prize announcement that he plans to devote the bulk of the money to follow up on clues to the workings of depression-related circuitry.

In his essay, Deisseroth explains how studies using optogenetics in rodents led to discovery of circuitry underlying the inability to feel pleasure from activities that are normally found enjoyable, or anhedonia – a core feature of depression.

“As a society, we must also work harder to prevent discouraging or dismissing scientists at the early stages of their careers with the wrong signals or inconstant support,” writes Deisseroth. “Just as with early-stage research, junior scientists are full of promise, unconstrained and vulnerable. The fullest reckoning of our community’s success can be measured in theirs.”

For More Information:

Karl Deisseroth wins 4 million euros Fresenius Research Prize

Scientists Switch Neurons On and Off Using Light

New Technique Pinpoints Crossroads of Depression in Rat Brain

Light Switches Brain Pathway On-and-Off to Dissect How Anxiety Works

Fat-free See-through Brain Bares All

New Views into the Brain

Channel Makeover Bioengineered to Switch Off Neurons

Slicing Optional

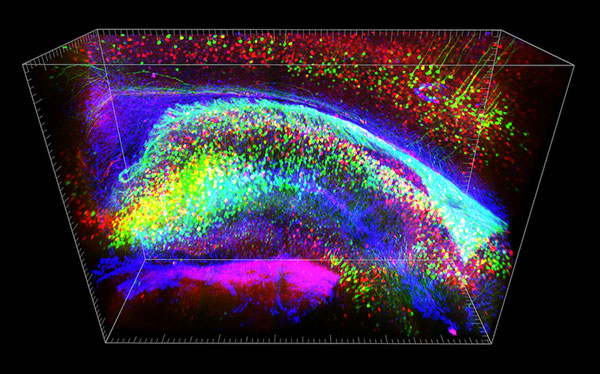

CLARITY image of hippocampus.

Source: Karl Deisseroth, M.D., Ph.D., Stanford University