Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health

Report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment

Department of Health and Human Services

Public Health Service

National Institutes of Health

National Institute of Mental Health

The National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment conducted these deliberations and prepared this report.

Recommended Citation:

The National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment. “Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health.” Washington, D.C.: 20001.

Single copies of this report are available through:

The National Institute of Mental Health

Office of Communications and Public Liaison

6001 Executive Boulevard, Room 8184

Rockville, MD 20892-9663

Telephone: 301–443–4315

Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Executive Summary and Recommendations

- I. A Look Backward: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Research

- II. A Look Forward: Current Emphases and Future Prospects for Child and Adolescent Intervention Research

- III. Infrastructure and Training

- IV. Future Directions for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Research

- V. Figures

- VI. Appendices

- VII. References

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the individuals listed below for their contributions to this report.

A special thank-you to all of the members of the National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment, whose dedication and hard work made this report a reality:

Chair

Mary Jane England, M.D.

Washington Business Group on Health

Members

William Beardslee, M.D.

Harvard Medical School

Marilyn Benoit, M.D.

Howard University Medical School & Hospital and Georgetown University Medical Center

Barbara J. Burns, Ph.D.

Duke University Medical Center

Ron Dahl, M.D.

University of Pittsburgh

Mary L. Durham, Ph.D.

Kaiser Foundation Hospitals

Graham Emslie, M.D.

University of Texas, Southwestern

Medical Center of Dallas

Michael English, J.D.

Center for Mental Health Services

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Robert Findling, M.D.

Case Western Reserve University

Robert Friedman, Ph.D.

University of South Florida

Jay Giedd, M.D.

NIMH Intramural Research Program

Regenia Hicks, Ph.D.

Department of Mental Health

Harris County, Texas

Robert L. Johnson, M.D., F.A.A.P.

New Jersey Medical School

Nadine Kaslow, Ph.D., A.B.P.P.

Emory University School of Medicine

Kelly Kelleher, M.D., M.P.H.

University of Pittsburgh

James Leckman, M.D.

Yale University Medical School

Martha Constantine Paton, Ph.D.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Paul M. Plotsky, Ph.D.

Emory University School of Medicine

John Weisz, Ph.D.

University of California Los Angeles

Roy C. Wilson, M.D.

Missouri Department of Mental Health

Mark Wolraich, M.D.

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Other Contributors to the Report:

Presenters

Deborah C. Beidel, Ph.D., A.B.P.P.

University of Maryland

Michael Davis, Ph.D.

Emory University School of Medicine

Mary Dozier, Ph.D.

University of Delaware

Peggy Hill, Ph.D.

Kempe Prevention Research Center for Family and Child Health, U. of Colorado, Denver

Isaac Kohane, M.D., Ph.D.

Harvard Medical School

David Olds, Ph.D.

Kempe Prevention Research Center for Family and Child Health, U. of Colorado, Denver

Sonja Schoenwald, Ph.D.

Medical University of South Carolina

NIMH Staff Director for Report

Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D., NIMH

Associate Director for Child & Adolescent Research

NIMH Staff for Report

Serene Olin, Ph.D.

Daisy Whittemore

NIMH Staff Contributors

Cheryl Boyce, Ph.D.

Rhonda Boyd, Ph.D.

Linda Brady, Ph.D.

Lisa Colpe, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Steve Foote, Ph.D.

Junius Gonzales, M.D.

Della Hann, Ph.D.

Themis Hibbs, Ph.D.

Ann Hohmann, Ph.D.

Doreen Koretz, Ph.D.

Israel Lederhendler, Ph.D.

Victoria Levin, M.S.W.

Ann Maney, Ph.D.

Douglas Meinecke, Ph.D.

Eve Moscicki, Sc.D., M.P.H.

Grayson Norquist, M.D., M.S.P.H.

Molly Oliveri, Ph.D.

Jane Pearson, Ph.D.

Kevin Quinn, Ph.D.

Heather Ringeisen, Ph.D.

Agnes Rupp, Ph.D.

Karen Shangraw Belinda Sims, Ph.D.

David Sommers

Jane Steinberg, Ph.D.

Ellen Stover, Ph.D.

Farris Tuma, Sc.D.

Ben Vitiello, M.D.

Lois Winsky, Ph.D.

Clarissa Wittenberg

With Special Thanks to NIMH Staff:

Karen May, Pamela Mitchell, and Catherine West

Consultants

Ellen Frank, Ph.D.

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Megan Gunnar, Ph.D.

University of Minnesota

Robin Peth-Pierce, M.P.A.

Health Communications Consultant

Roland Sturm, Ph.D.

RAND Health

Eva M. Szigethy, M.D., Ph.D.

Judge Baker Children’s Center

Preface

May 2001

Dear Dr. Hyman:

On behalf of my council colleagues, Drs. Mary Durham and Roy Wilson, it is my pleasure to present to the National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC) the report of the NAMHC Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment. Our workgroup has been inspired by the historic amount of public attention on children’s mental health. This intense interest is apparent in the number of activities that have been undertaken to illuminate progress and identify problems in this area.

All these efforts, ranging from White House conferences and Surgeon General reports to private foundation publications, have arrived at the same conclusion: Findings from research in neurobiology, genetics, behavioral science, and social science have led to an increased understanding of the complex interactions among genetic and socioenvironmental factors and their contribution to child and adolescent mental disorders. Further, a promising number of scientifically proven preventive interventions and treatments are now available. Yet, children, adolescents, and their families continue to suffer enormous burdens associated with mental illness—burdens that are often intergenerational. The central problem is that these scientifically proven interventions are not routinely available to the children and their families who need them. The interventions often fail to take into account the diverse sociocultural context and settings in which they will be implemented and are consequently not sustainable. At the same time, the majority of treatments and services children and adolescents receive in the community have either not been evaluated to determine their effectiveness or are simply ineffective. The gap between research and practice continues to widen; part of closing the gap entails investigating the best methods for deploying evidenced-based approaches in real-world settings.

Our ability to create a promising future for the country depends, in part, on our ability to ensure that all children have the opportunity to meet their full potential and live healthy, productive lives. Meeting this challenge will require the work of many people. The research community must partner with families, providers, policymakers, and Federal agencies providing children’s services, as well as other stakeholders, to create a knowledge base on interventions and services that is usable, disseminated, and sustained in the diverse communities where children and their families live. Equally important to this effort is the need to develop the capacity of the field. A new generation of truly interdisciplinary researchers must be trained to strengthen the science base on child and adolescent mental health research and bridge the gaps within and across research, practice, and policy.

We appreciate the opportunity to provide this report. Together with key stakeholders, and with your help, we hope to chart a new course for the future of child and adolescent mental health research.

Sincerely,

Mary Jane England, M.D., Chair, NAMHC Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment

Executive Summary and Recommendations

In the United States today, one in 10 children and adolescents suffers from mental illness severe enough to result in significant functional impairment. Children and adolescents with mental disorders are at much greater risk for dropping out of school and suffering long-term impairments. Recent evidence compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that by the year 2020, childhood neuropsychiatric disorders will rise by over 50 percent internationally to become one of the five most common causes of morbidity, mortality, and disability among children. These childhood mental disorders impose enormous burdens and can have intergenerational consequences. They reduce the quality of children’s lives and diminish their productivity later in life. No other illnesses damage so many children so seriously.

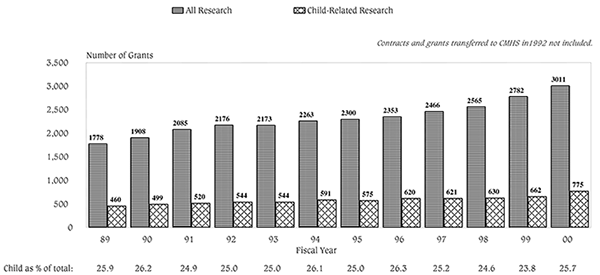

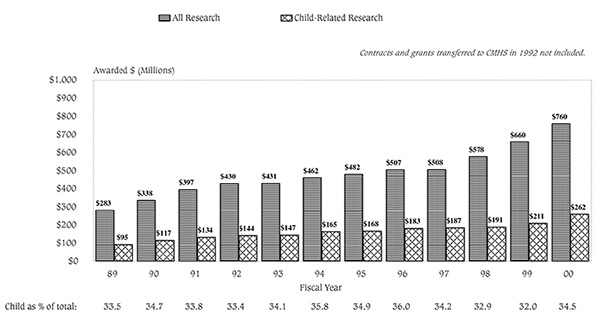

In light of the pressing needs of children and adolescents with mental illness, the NAMHC recommended to NIMH Director Steven Hyman, M.D., that a Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment be established. Dr. Hyman charged this group with reviewing research and training, specifically (1) assessing the status of the NIMH portfolio and identifying research opportunities in the development, testing, and deployment of treatment, service, and preventive interventions for children and adolescents in the context of families and communities; (2) assessing the human resource needs in recruiting, training, and retaining child mental health researchers; and (3) making recommendations for strategically targeting research activities and infrastructure support to stimulate intervention development, testing, and deployment of research-based interventions across the child and adolescent portfolio. This report is the result of their work over the past year.

Ten years ago, after the Institute of Medicine released the report “Research on Children and Adolescents with Mental, Behavioral and Developmental Disorders” (IOM, 1989), the NIMH issued a “National Plan for Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders,” which helped shape the current research agenda. As a result of this national plan, research in the field of child and adolescent mental health has expanded dramatically. Much has been learned about the identification and treatment of mental illness in children. But many issues remain unresolved. Stigma continues to be a significant barrier to mental health treatment for children and their families, despite public education efforts. Scientifically proven treatments, services, and other interventions do exist for some conditions but are often not completely effective. Most of the treatments and services that children and adolescents typically receive have not been evaluated to determine their efficacy across developmental periods. Even when clinical trials have included children and adolescents, the treatments have rarely been studied for their effectiveness in the diverse populations and treatment settings that exist in this country.

Finally, those interventions that have been adequately tested have not been disseminated to the children and their families who need them, nor to the providers who can deliver them. Services for children are often fragmented, and many of the traditional service models do not meet the needs of today’s children and families. In sum, there is a shortage of evidence-based treatment, and much of the evidence that does exist is not being used. As a result, the burden of mental illness among children and adolescents is not decreasing.

In the past few years, this burden has not gone unnoticed. There has been heightened activity in this area, launched by the issuance of the landmark document “Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General” (U.S. Public Health Service, 1999), which included a chapter focused on the mental health needs of children. This seminal report marked a turning point in the public focus on mental health by clearly documenting the pressing public health need for effective mental health services and highlighting the scientific advances that now offer hope for individuals with mental illness. An offshoot of that effort, “A Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda” (2000), provided a blueprint for children’s mental health research, practice, and policy. In addition, “The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide” (1999) provided a plan to increase awareness and prevent suicide in the United States. Several other reports contributed to this escalating national dialogue, including “Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General” (U.S. Public Health Service, 2001), which reviewed the scientific literature on the cause and prevention of youth violence; “A Good Beginning” (Child Mental Health Foundations and Agencies Network, 2000), a monograph on the importance of children’s socioemotional school readiness; and “From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development” (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000).

This intense national interest in children’s mental health has arisen, in part, from the rapidity of research advances in neurosciences, genetics, behavioral sciences, and social sciences. Progress in developmental neuroscience and genetics, for example, is beginning to illuminate how the brain functions at the molecular, cellular, and neural systems levels. Similar advances have been made in the basic behavioral sciences and in clinical treatment and prevention research targeted at specific childhood disorders. Some of the key findings that will help guide future research are listed below; for an overview of advances in the specific research areas, see Section II.B., Key Scientific Areas of Research.

A Decade of Progress: Key Findings in Neuroscience, Behavioral, Prevention, and Treatment and Services Research

- The impact of genes on behavior is complex; multiple genetic and nongenetic factors interact to produce cognitive, emotional, and behavioral phenotypes. Genes and the environment interact throughout development in ways that are not simply additive; for example, genes influence the nongenetic aspects of development (covariance).

- A child’s environment, both in and out of the womb, plays a large role in shaping brain development and subsequent behavior. Studies of the caregiving environment suggest that extreme environments (such as abuse and neglect) may affect brain cell survival, neuron density, and neurochemical aspects of brain development, as well as behavioral reactivity to stress in childhood and adulthood. Methods to understand the more subtle effects of the environment on synapses and circuits are likely to become available in the near future.

- Research has demonstrated the remarkable plasticity of the brain and, in certain neural systems, the ability of the environment to influence neural circuitry during childhood.

- Researchers have found that difficulties with attentional self-regulation can contribute to behavioral problems and difficulties in school; research tracing normal development and individual differences in these regulatory controls has important implications for advancing understanding of the causes of a variety of childhood disorders in which regulatory deficits are implicated (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], mood and anxiety disorders).

- Progress has been made on the identification of developmental models that describe how cumulative risk factors contribute to adjustment problems and mental disorders, including conduct problems, substance abuse, high-risk sexual behavior, and depression. Risk factor studies have identified some potent and malleable targets.

- New methodological designs and statistical techniques have been developed to strengthen prevention trials (which are complex by their very nature) and have provided a conceptual basis for designing and evaluating prevention programs.

- Effective treatments, both psychosocial and psychopharmacological, have been developed to improve outcomes for some children and adolescents.

- Research has now documented that psychosocial interventions and services may also enhance the impact of pharmacological treatment.

- Advances in medication treatment are especially promising for several child and adolescent disorders, including ADHD, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), other anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, and social phobia), and adolescent depression.

- Major studies are currently underway to test the benefits of psychotherapy, medication, and combined treatment for selected major mental disorders affecting youth.

- Medication management and combined treatments (medication plus behavior therapy) for children with ADHD have been found to be effective in targeting core ADHD symptoms. Combined treatments are effective in improving non-ADHD symptoms (e.g., disruptive behaviors and anxiety symptoms) and functional outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, parent-child relations, and social skills).

- Multisystemic therapy (MST), a treatment approach that addresses both the individual child and the child’s context, is another promising intervention. Multiple trials have indicated beneficial effects of MST for youth with conduct problems. Positive outcomes include decreasing externalizing symptoms and improving family functioning and school attendance.

- Research has also identified treatments that are potentially ineffective or, worse yet, harmful. Some forms of institutional care do not lead to lasting improvements after the child is returned to the community. Some services provided to delinquent juveniles are also ineffective (e.g., boot camps and residential programs); peer-group-based interventions have been found to actually increase behavior problems among high-risk adolescents.

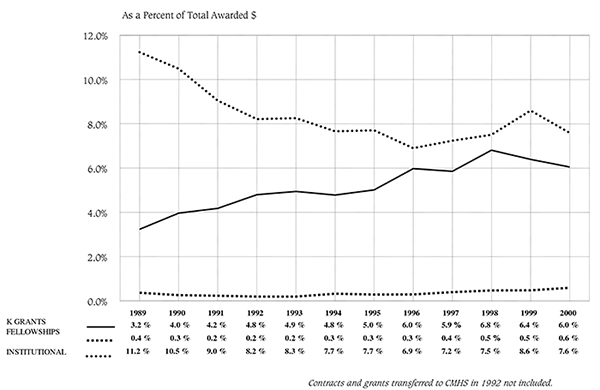

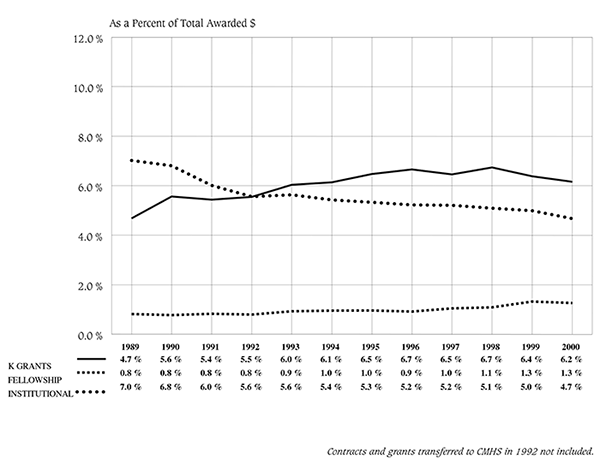

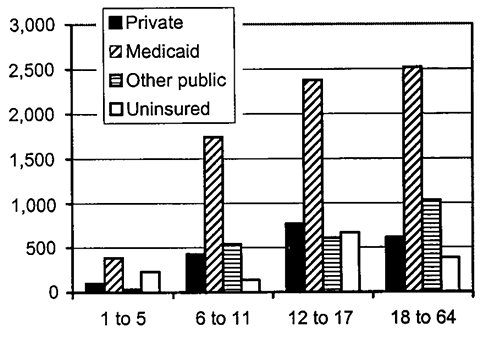

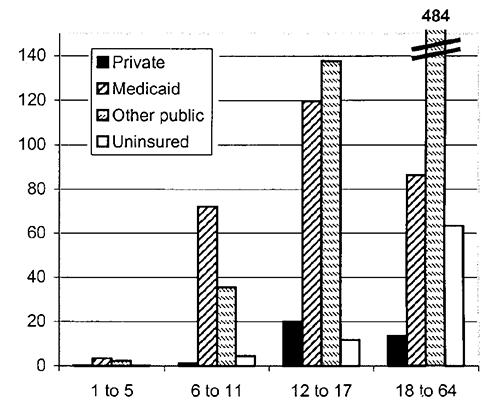

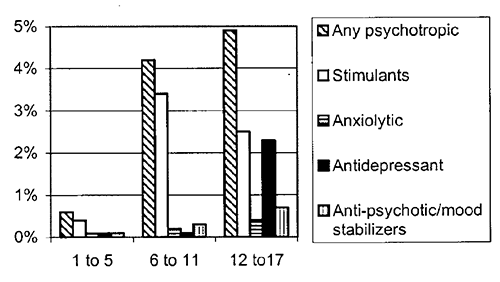

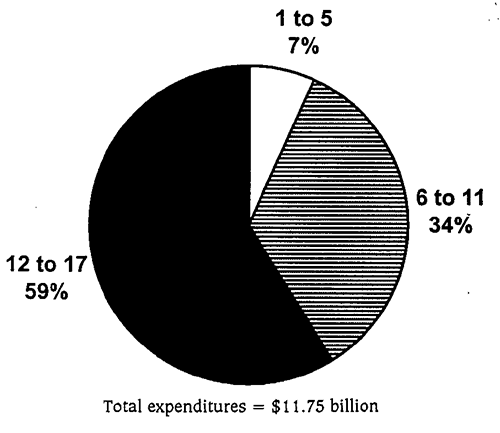

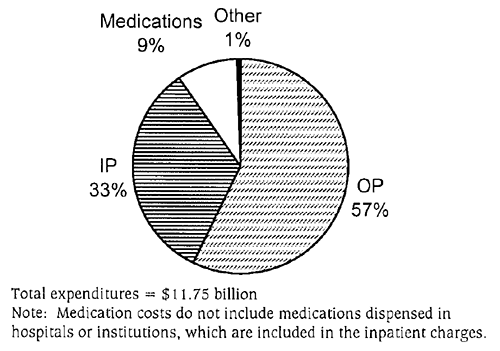

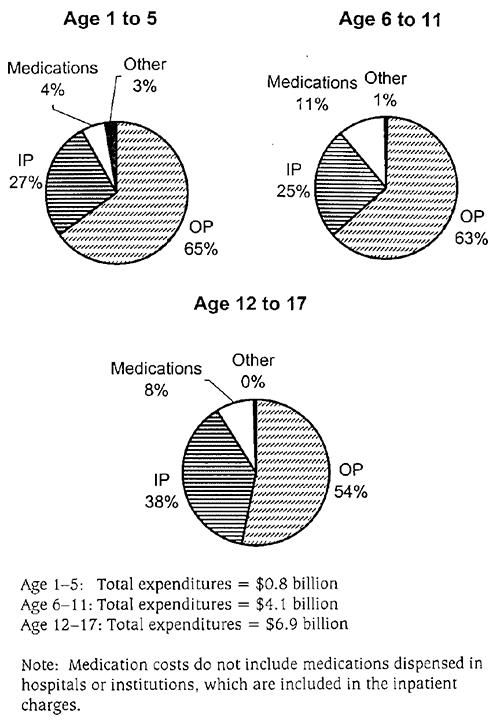

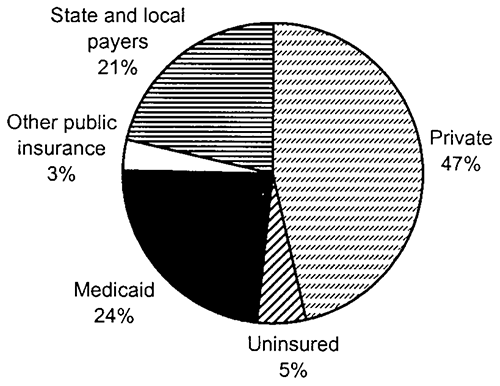

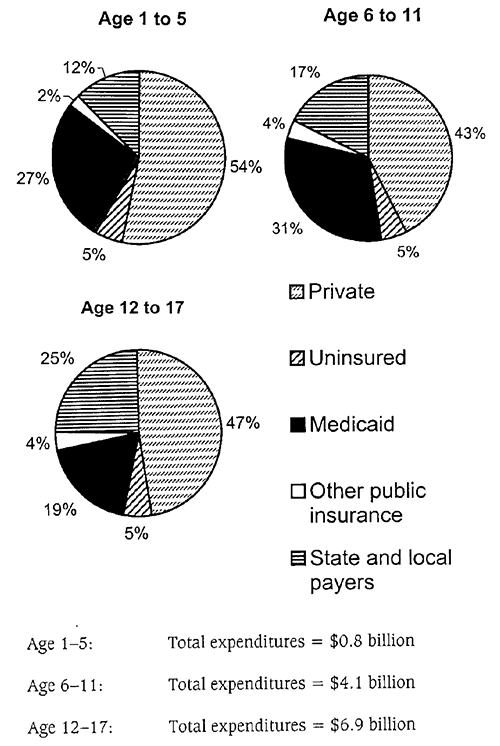

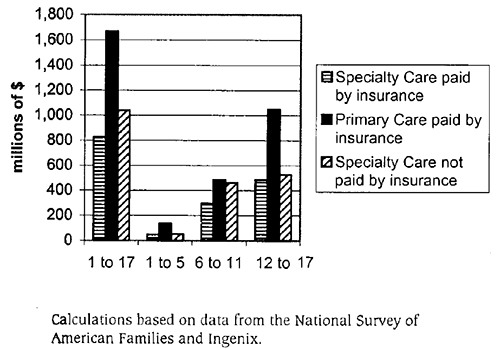

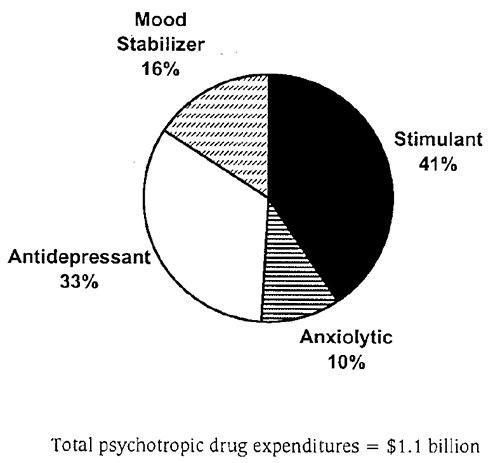

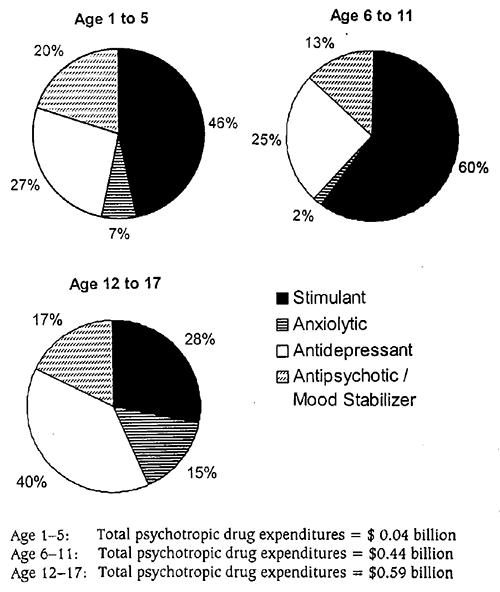

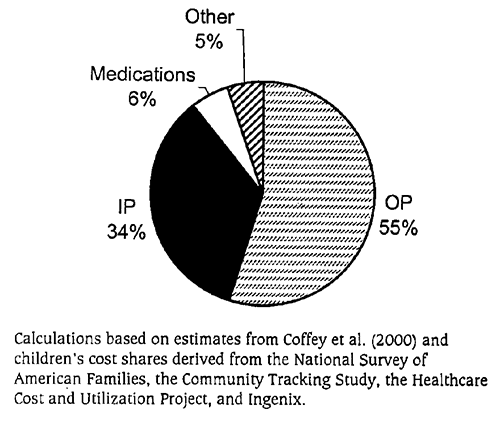

- Research on mental health economics has provided more accurate data on expenditures for mental health services in specialty mental health and general health sectors; 1998 annual expenditures were $11.75 billion, or about $173 per child. This is nearly a threefold increase from the 1986 estimate of $3.5 billion (not accounting for inflation).

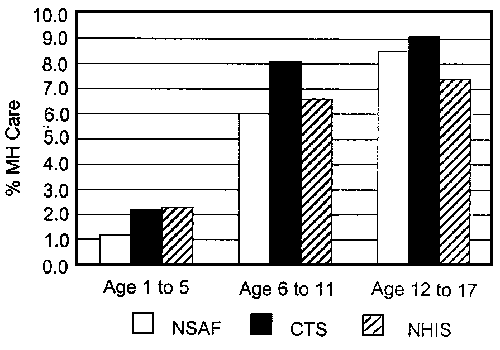

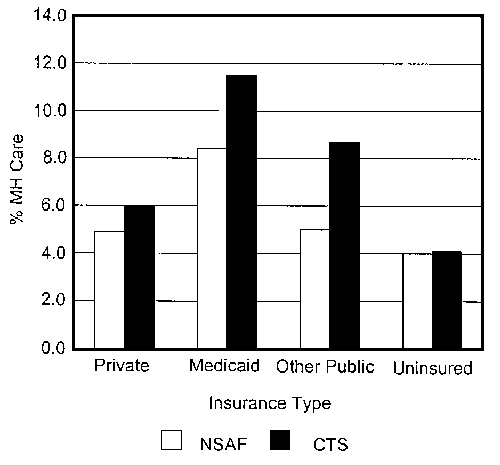

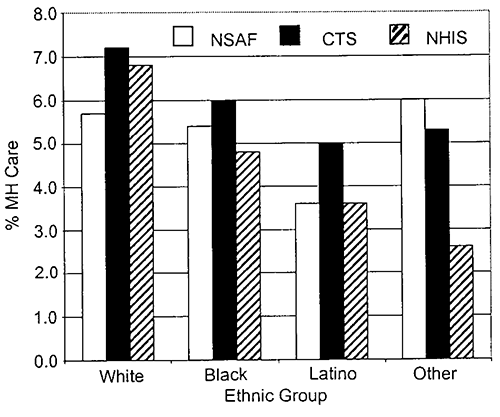

- New utilization data indicate that there is an increase in the rate of outpatient mental health service use since the 1980’s; however, only 5 percent to 7 percent of children receive some specialty mental health services, in contrast to an estimated 20 percent with a diagnosable mental disorder.

The Challenges: Developing Effective Prevention Programs, Treatments, and Services

In a field as complex as children’s mental health, developing effective solutions requires coordinated efforts within and across multiple disciplines. The research advances highlighted above, coupled with growing knowledge about clinical interventions and services afford an opportunity for interdisciplinary exchange and integration of knowledge across a range of specialized research areas. However, several issues complicate efforts to undertake interdisciplinary work in the field of child and adolescent mental health.

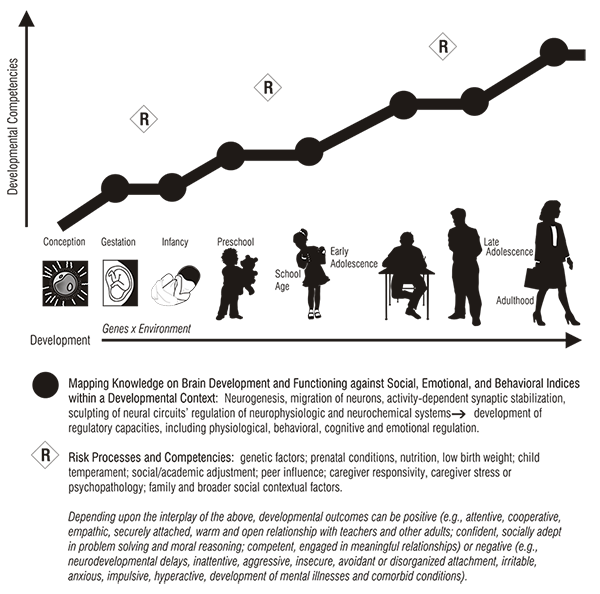

Development

Children’s rapid growth and development greatly amplifies the complexity of interdisciplinary research. Integrating this developmental perspective is critical to advancing research on child and adolescent mental illness, prevention, treatment, and services. Childhood is characterized by change, transition, and reorganization; understanding the reciprocal influences between children and their environments throughout the developmental trajectory is critical.

Social Context

Another issue that impedes progress is the fact that few of the evidence-based interventions have taken into account the child’s social context. For example, the social context has not been studied in sufficient detail to know whether interventions can be generalized across populations, settings, or communities. The majority of studies on child and adolescent mental health interventions have not attended to differences in race, ethnicity, culture, socioeconomic status, community/neighborhood context, and wider systemic issues. Attending to these factors is critical, particularly for children and families living in poverty. Inattention to these issues becomes most apparent when stakeholders, including families, providers, payers, and community leaders, ask about the relevance of research findings for their communities or populations. While knowledge about the efficacy of treatments is increasing at a rapid rate, the effectiveness and transportability of these treatments to diverse populations and settings are less clear.

Disciplinary Insularity

Another challenge is the insularity of the many disciplines involved in clinical and research training. This insularity threatens to impede progress at precisely the time when rich opportunities for interdisciplinary work exist. For example, the following disciplines are likely to have some component of training relevant to the mission of this report: Psychiatry, pediatrics, developmental and behavioral pediatrics, adolescent medicine, nursing, epidemiology, developmental neuroscience, cognitive and behavioral neuroscience, social work, clinical psychology, developmental psychology, and developmental psychopathology. Other fields that can contribute significantly include public health, anthropology, and economics. Because of the rigors and traditions within each area, it can be extremely difficult to create training programs that cross these boundaries.

Clinical care providers (e.g., pediatricians, family medicine physicians, pediatric nurses, psychiatric nurses, social workers, and others) are also critical to this partnership. The insularity of disciplines that presents research barriers also affects the adoption of research findings in practice settings; it is unlikely that treatment practices developed in one discipline will find their way into other professional disciplines. The fragmentation of systems serving children with mental health needs further complicates interdisciplinary efforts. Thus, clinical providers in primary care are unlikely to adopt mental health screening or early intervention methods developed in child psychology or psychiatry, even though such knowledge may be critical to child mental health promotion and early intervention efforts.

Compounding the problem of insularity is the decline over the past 10 years in the number of new investigators seeking research careers to study child and adolescent mental health. Reports from associations representing child and adolescent physicians suggest that dwindling numbers are choosing to enter research careers. To strengthen the science base on child and adolescent mental health, the research-training infrastructure must be enhanced to support a cadre of investigators who can conduct interdisciplinary research to bridge the gaps among research, practice, and policy.

Overcoming the Obstacles: Establishing Linkages

Despite these obstacles, the prospects for gaining a deeper understanding of the complexities of child and adolescent mental illnesses—what causes them, what interventions are effective, and how to get these interventions to those who need them—are better now than at any time in the past. This report enters the ongoing national conversation and proposes the use of new models for integrating basic research with intervention development and service delivery. It also underscores the importance of using a developmental framework to guide research in child and adolescent intervention development and deployment. Two critical action steps must be taken to move ahead:

- Linkages must be made among neuroscience, genetics, epidemiology, behavioral science, and social sciences, and the resulting interdisciplinary knowledge must be translated into effective new interventions.

- Scientifically proven interventions must be disseminated to the clinics, schools, and other places where children, adolescents, and their parents can easily access them. This means that the science base must be made usable. To do so will require partnerships among scientists, families, providers, and other stakeholders.

While many of these issues have been discussed in other recent reports, among the most important contributions of this report are the strategies it provides to overcome the obstacles outlined above and the direct application of these strategies to child and adolescent populations. This report suggests ways to integrate previously isolated scientific disciplines, with the goals of both creating an interdisciplinary and well-trained cadre of child and adolescent researchers and strengthening the currency of mental health science. This report also provides strategies for linking basic science findings to the development of new interventions and ensuring that they are positioned within the context of the communities in which they will ultimately be delivered. Doing so requires the utilization of a new model of intervention development, wherein factors influencing the ultimate dissemination of the intervention are considered from the start.

Priority Area 1: Basic Science and the Development of New Interventions

The linkages among neuroscience, genetics, epidemiology, behavioral science, and social sciences provide opportunities for increasing our understanding of etiology, attributable risk, and protective processes (their relative potency, sequencing, timing, and mechanisms). Such knowledge is critical for the creation of developmentally sensitive diagnostic approaches and theoretically grounded interventions. One critical piece of knowledge needed is an understanding of the etiology of mental illnesses, which can lead to better identification of “high-risk” groups as the target for these early interventions, as well as “high-risk” or vulnerable intervals in development. Despite our appreciation of developmental perspectives, many evidence-based interventions for children and adolescents continue to represent downward extensions of adult models, with limited consideration of basic knowledge about how causal mechanisms or processes operate or may vary across developmental or sociocultural contexts. Conceptual approaches and developmental theories are needed to guide intervention and dissemination efforts. Information from developmental neuroscience, behavioral science, and epidemiology should be used to formulate competing and testable hypotheses about those developmental processes that lead to mental disorders. At the same time, knowledge gleaned from intervention testing and dissemination research must inform basic research theory and development.

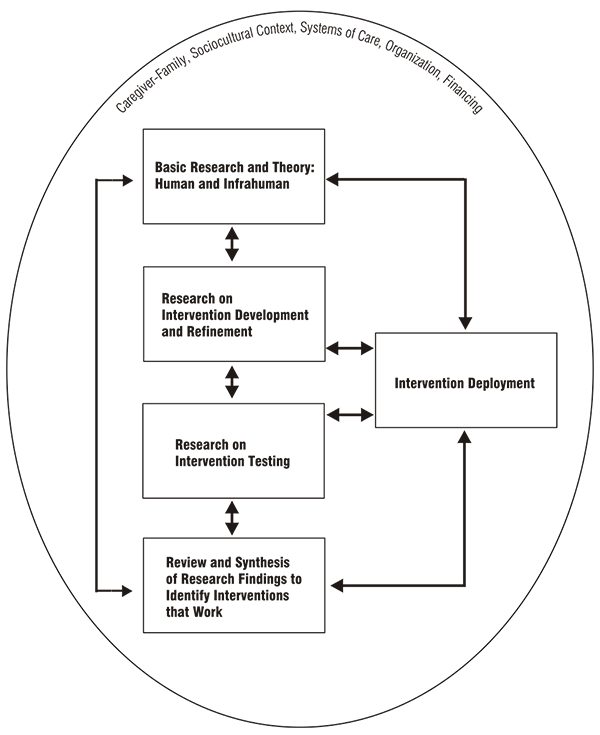

Priority Area 2: Intervention Development, Moving From Efficacy to Effectiveness

The current model of treatment development (typically followed in biomedical science studies) stipulates that such development begin in laboratory settings; that highly specific sample selection criteria be used; that refinement, manualization or algorithm development, and delivery be carried out by research staff (as opposed to practicing clinicians); and that aspects of the service setting where it is ultimately destined to land be ignored. This model creates an illusion that science-based treatments are not meant to be used or usable. This report suggests that a different model of intervention development be followed. This new model requires two strands of research activity: The first strand necessitates a closer linkage between basic science and clinical realities (as described in Priority Area 1); the second strand requires that a focus on the endpoint and its context—the final resting place for treatment or service delivery—be folded into the design, development, refinement, and implementation of the intervention from the beginning. Furthermore, such interventions should be developmentally sensitive and take into account family and cultural contexts. Finally, in order to explain why treatments work, it will be important to identify core ingredients of the intervention, including the mechanisms that led to therapeutic change and the processes that influenced outcomes.

Priority Area 3: Intervention Deployment, Moving From Effectiveness to Dissemination

For evidence-based interventions to be used in clinical practice, knowledge about effective dissemination strategies is needed. The application of the traditional biomedical model of intervention development, described above, does not necessarily lead to interventions that are adaptable, applicable, or relevant to real-world clinical practices. To ensure that the current evidence base is used appropriately, a new genre of scientific effort is needed to better understand factors that influence the transportability, sustainability, and usability of interventions for real-world conditions. Many promising preventive and treatment interventions have not paid enough attention to factors that influence family engagement in services, for example, nor to the broader socioecological contexts and systemic issues that influence access to and use of such services. Such research is critical if the current evidence base on effective interventions is to be brought to scale, sustained in service settings, and made accessible to the children and families in need.

Interwoven among these priorities is the critical need to support interdisciplinary training. To ensure that the next generation of scientists is prepared to integrate the rapid advances in multiple disciplines, interdisciplinary training must be made an integral part of future child and adolescent mental health research.

The Future of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Research

The development and dissemination of new, research-based mental health interventions for children and adolescents will require that scientists create partnerships with community leaders, families, providers, and other stakeholders. Thoughtful scientific partnerships will also need to be forged across different scientific disciplines if the power and promise of basic neuroscience and behavioral science is to be realized through improvements in clinical care. Significant challenges exist: The ethical complexities underlying new research advances will necessitate careful application of oftentimes elusive principles. Such complexities must be thoughtfully resolved. Furthermore, the rapid pace of technological advances will make it possible to move services away from traditional settings and into innovative venues, such as the Web, chat rooms, or other nonclinic settings. But new technology brings new scientific and practical challenges, and these, too, will require careful deliberation.

This report describes a 10-year plan for advancing research on child and adolescent mental health interventions. This report, framed within a public health perspective and supported by taxpayer dollars, will have merit only insofar as it leads to improvements in the quality of care children and adolescents receive, and thus improvements in the quality of the lives they lead. The toll that preventable, untreated, or poorly treated mental illness takes on children, adolescents, and their families is profound and unacceptable. In the past 10 years a vast amount of knowledge has been garnered about the prevention, identification, treatment of, and services for mental illnesses in children and adolescents. This knowledge can and should be used to improve care. But in the next decade, we must be more exacting. The next generation of child and adolescent mental health science will require a transformation of form, function, and purpose if a true public health model is to be realized and sustained.

Recommendations

To mark this new generation of research, the next section describes the workgroup’s recommendations in three broad areas. The first is the area of interdisciplinary research development on child and adolescent interventions. Recommendations in this section are designed to create interdisciplinary research networks and establish a forum for the creative exchange of collaborative research projects to foster new approaches to common problems. The focus of these networks should be on targeted problems, the solution to which may lie outside the scope of a single discipline. The second area is focused on developing new training initiatives to build a cadre of high-caliber scientists to tackle future problems in child and adolescent mental health. Interdisciplinary research training is needed to provide multiple perspectives on intractable problems. Because we recognize that the viability of such interdisciplinary efforts depends, in part, on continuing advances in specific scientific disciplines, the third set of recommendations is targeted toward advancing programs of research in particular areas. Implementation of all three sets of recommendations may have to be staged and focused to accomplish the goal of disciplined growth.

I. Interdisciplinary Research Development in Child and Adolescent Mental Health

A. Child and Adolescent Interdisciplinary Research Networks (CAIRNs)

We recommend that NIMH create support for the implementation of Child and Adolescent Interdisciplinary Research Networks (CAIRNs) to strengthen and accelerate research on intervention development and deployment. The goals of this initiative are to create a series of interdisciplinary research networks that include research-training support and to encourage collaborative research among scientists from different institutions and disciplines. The primary purpose of the CAIRNs will be to introduce new approaches to common problems and support collaborative and integrative research activities across scientific fields.

We recommend that three types of networks be developed, congruent with the research agenda and mission of NIMH: (1) Developmental Basic Science and Clinical Intervention Networks, (2) Treatments and Services Practice Networks, and (3) Implementing Evidence-based Practice Networks. These three sets of networks are targeted at different sets of research problems in the field of child and adolescent mental disorders. The networks should be set up flexibly to encourage interdisciplinary and integrative activities on shared research goals. The aim of the networks is to provide a framework to foster the development of integrative research teams and to provide flexibility for addressing complex scientific questions.

1. Developmental Basic Science and Clinical Intervention Networks (DBCIs)

These networks would focus on linking developmental processes to basic neuroscience or behavioral science, with an explicit focus on creating new assessment models and interventions. These networks will concentrate on underdeveloped areas that hold promise for understanding developmentally sensitive transition points in children’s lives. An overarching goal will be to map extant knowledge about the functioning of the brain against current behavioral indices within a developmental context. The purpose is not to encourage observational studies of risk factors but rather to develop testable models for enhancing etiologic understanding of disorders, to improve assessment strategies, and to develop new treatment models. DBCI networks could address the following research topics:

- Early environment factors (prenatal and postnatal) that influence the development of neural systems involved in attention, impulsivity, and disruptive behavior

- Behavioral and neurobiological deficits in autistic spectrum disorders (e.g., social cognition as it relates to brain activity and the development of behavioral and pharmacologic interventions for improvement of autistic symptoms)

- Neural bases of habitual or repetitive behaviors

- Effects of stress on brain and behavior development as it relates to the regulation and dysregulation of mood and emotions

- Extinction of fear and regulation of anxiety

- Interactions among temperament, mood, emotion, and cognition (e.g., attentional processing) and their implications for behavioral and learning difficulties

2. Treatments and Services Practice Networks (TSPs)

To encourage interdisciplinary research on the development of new treatments, Treatments and Services Practice Networks (TSPs) should be created. These networks could provide support to facilitate the development of culturally sensitive treatments that are feasible, cost-effective, and readily disseminated. These networks could combine basic science expertise with clinical and services expertise to answer questions related to improving treatment efficacy, effectiveness, and delivery within routine practice. These networks should reflect family, youth, and practitioner input on questions of interests and outcomes. Such networks could include (a) treatment development in partnership with practice communities to create new interventions within service settings, (b) the expansion of treatment trials into routine practice settings, or the (c) expansion of the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPPs). TSPs could address the following research topics:

- Development of treatment algorithms for clinical decision-making

- Development of triage guidelines to tailor severity of clinical problems to dosage, intensity, or types of treatments or services

- Development of new psychosocial treatments for delivery within primary care, school-based health clinic, or other community practice settings

- Development of psychosocial treatments that attend to the social-ecological environment of the child and his/her family

3. Implementing Evidence-based Practice Networks (IEPs)

These networks would focus on linking evidence-based interventions to dissemination, financing, and policy research. The Implementing Evidence-based Practice Networks (IEPs) would examine the application of dissemination and quality improvement strategies for implementing the scientific knowledge base on evidence-based practices for children and adolescents. While the TSPs are designed to develop new treatments and services through connections among basic scientists and providers, the IEPs would focus on studying how empirically supported interventions that already exist (or will exist) can be effectively deployed, sustained, and implemented in diverse communities, with particular attention to cost-effectiveness and quality. The translation would focus on moving efficacy-based findings into a range of practice settings and specifically on encouraging interdisciplinary studies among health economists, behavioral, services and clinical scientists. Critical to this translation is the role of youth and families in defining implementation strategies. The following issues might be the focus of such networks:

- Use or adaptation of empirically tested treatments in community clinic settings where usual care has not previously included such treatments

- Application of evidence-based assessment tools or preventive interventions with young children

- Use of evidence-based practice in primary care and in school-based health clinics

- Use of depression screening and evidence-based treatment for depression in a variety of settings

- Implementation of parenting education in primary care settings

- Studies of factors influencing how practitioners and families manage youth disorders and the use of evidence-based treatments

B. Overall Structure and Characteristics of Networks

- We recommend that all three of these networks include research infrastructure support to enable trainees and junior faculty to obtain training and mentorship in the networks. As feasible, these could be integrated with existing mechanisms. Additional training recommendations are described below in Section II, Interdisciplinary Research Training in Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

- We recommend that the proposals submitted in response to the initiative on CAIRNs be reviewed in-house at NIMH and not through the Center for Scientific Review (CSR). Regardless of the location of the review, program staff should work in conjunction with Scientific Review Administrators (SRAs) to inform Institutional Review Groups (IRGs) about these areas of emphasis.

- Although the three types of networks are focused on different sets of research problems, we recommend that the directors of all the networks meet annually to share research advances, to strengthen training opportunities among the networks, and to plan for expansion or refinement of their interdisciplinary studies. Trainees should be invited to these annual meetings.

- We recommend that NIMH consider co-sponsorship from other Federal agencies in developing and funding these CAIRNs, where appropriate.

II. Interdisciplinary Research Training in Child and Adolescent Mental Health

A. Capacity Building

- We recommend that NIMH develop a payback program whereby individuals who pursue careers in child and adolescent research may apply for loan forgiveness.

- We recommend that NIMH develop additional mechanisms to support mentoring for new research scientists in child and adolescent mental health. This program may include funding for sabbatical leaves or teaching/mentoring time, provided in the form of supplements to grants. Funding for teaching/mentoring time is critical because there are so few clinical investigators, all with multiple demands on their time.

- To build the research capacity needed to take advantage of the promise of interdisciplinary research, we recommend that NIMH issue a new initiative for the creation of Child and Adolescent Interdisciplinary Training Institutes (CITIs). Basic requirements would include training or exposure in at least the following scientific areas: basic behavioral and neuroscience, epidemiology, prevention, intervention development, services research, and health economics. Training seminars, summer institutes, and intensive coursework on methodology, statistics, and the range of service settings where mental health services are typically delivered (e.g., schools, primary care, community clinics) would be required. To initiate CITIs, we recommend that NIMH establish one or two pilot educational research experiences in interdisciplinary and developmental research with the explicit focus of encouraging child and adolescent studies. The overall purpose would be to work out pragmatic and feasibility issues in detail in at least one or two universities on how to effectively integrate basic and clinical training for clinically oriented investigators. Successful pilot programs would serve as models for further interdisciplinary training programs. We also recommend that the directors of the CITIs meet annually to discuss training initiatives and new programs and to modify educational objectives as needed.

- We recommend that a special announcement be issued for child and adolescent research supplements. Modeled along the lines of minority supplements, they would be used to encourage investigators in other fields (e.g., adult mental health, primary care, education, neurology) to receive training in child and adolescent mental health and thus increase the numbers of investigators with expertise in child mental health research.

- We recommend that NIMH develop a national mentorship program to increase the number of racial/ethnic minorities among NIMH-funded trainees who can address the unique needs of minority children. This mentorship program could include the NIMH Intramural Research faculty. Such an effort is critical in light of changing demographics; minority children are increasingly represented among those with significant mental health needs.

B. Partnerships To Facilitate Research Training

To enhance child and adolescent research training activities, NIMH should explore opportunities to partner with other Federal agencies. Potential partners include the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Health Research and Services Administration (HRSA); the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) and the Center for Substance Abuse and Prevention (CSAP), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). For example, NIMH should consider MCHB’s Leadership in Education in Neuro-developmental Disabilities (LEND) programs as an avenue for including more of a mental health perspective.

III. Recommendations for Program Development in Specific Research Areas

A. Neuroscience

- We recommend that databases of rodent and human brain maps be established and supported. We particularly emphasize that these databases need to have a developmental dimension.

- We recommend that cross-institute initiatives be fostered to establish genomic databases.

- We recommend funding program projects to bring together investigators from a variety of disciplines to examine the developmental effects of well-recognized conditions (e.g., stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [HPA] system).

- We recommend that technological and procedural advances be supported that (a) allow scanning of very young normal children, (b) enable the development of non-invasive imaging procedures that can be used on awake behaving primates, and (c) encourage the development of functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which can image potentially powerful rodent models of genetic disease.

- Integrative approaches to studies of brain development and function are needed. Examples include (a) combining techniques of neuroimaging with simultaneous physiological monitoring and/or emotional testing, hormonal measurements, and so on; (b) electrophysiology at both the single-cell and multiunit levels to study molecular and circuit regulation in animal models of behavioral dysfunction; and (c) mutant animal models that allow researchers to study epigenetic determinants of brain development (e.g., constitutively manipulated mice may reveal compensatory developmental changes relevant to behavior).

- A major gap exists in the availability of data relating developmental trajectories across multiple levels of description, from genetic processes to behavioral competencies. Data are needed in the following areas:

- Cross-species differences and correspondences in neural and behavioral development, the impact of differing genetic backgrounds, and the validity of various phenotyping procedures in animals as behavioral markers of psychopathological outcomes.

- Gender differences and the putative actions of gonadal steroids, changes in neurocircuitry with puberty, and their relationship to cognitive, behavioral, and emotional regulation during adolescence.

B. Behavioral Science

- Research is needed on how different components of cognition (e.g., attention, language, memory, social) develop in normative and clinical groups of children in order to shape intervention and preventive strategies. This research can increase our understanding of how children with cognitive deficits associated with mental illness may benefit from intervention efforts and perhaps develop new or compensatory skills. Such studies have implications for the prevention or development of more severe impairments or comorbid conditions.

- We recommend detailed empirical study of the specific psychological and behavioral functions that are impaired in childhood mental disorders. Critical domains include memory, attention, emotional processing, emotional expression, social cognitive capacities, and several dimensions of child temperament. Specifying the nature of disorders in terms of these domains will not only improve nosology, but it will also be critical in making connections to neural substrates and in identifying genetic and experiential factors in etiology. As a result, such an effort will pave the way for the design and implementation of increasingly well-targeted modes of preventive and treatment intervention.

- We recommend research focused on developmental, behavioral, and social regulators of emotions at key transition periods, such as birth and puberty, and social transitions, such as daycare and elementary school.

- We recommend the development of science-based interventions that link the psychophysiological deficits associated with mental disorders (e.g., attention, information processing) with specific functional problems, with the aim of formulating more effective and targeted intervention strategies.

- We recommend that NIMH support the development of measurements of functioning that are both culturally sensitive and multidimensional. New tools and approaches that combine qualitative and quantitative methods are needed to understand issues associated with children from diverse cultures and subcultures. In addition, measurements are needed that complement traditional symptom-based diagnostic systems and serve as outcome indicators in intervention, services, and risk processes research.

- We recommend developing measures and interventions through ethnography. The diagnostic conundrums that plague childhood nosology and the pervasive concern about labeling young children suggest that rigorous ethnographic or other qualitative methods for describing mental illness may be particularly useful in developing interventions that are sensitive to a variety of living environments, communities, and cultural contexts.

- We recommend new behavioral research to identify how providers and families manage children’s disorders and why they do or do not engage in the most effective practices. Behavioral science has significant promise to reveal why treatments are not more widely disseminated, what factors underlie complex health behaviors, and the types of decision-making strategies that guide current practice.

C. Prevention

- We recommend that attention be paid to smaller, focused, and intensive longitudinal studies, informed by basic research.

- Given the extensive number of data sets examining risk and protective factors, we recommend that a workshop be convened to identify opportunities for reanalysis of existing data sets. Examples of questions for such studies would include areas of attributable risk, predictors of resilience, interaction of different types/levels of risks across time, how impairment is affected by context, and the impact of contextual and cultural variables on functioning over time.

- A new emphasis is needed on prevention effectiveness trials, prevention services, and cost-effectiveness of preventive strategies. Studies that focus on service contexts that facilitate or impede the sustainability of preventive interventions are especially needed.

- Prevention research trials, by their nature, require longitudinal follow-up and the use of fairly sophisticated efforts to determine the effects of the interventions. Support for methodology development, especially the analysis of longitudinal data where the phenomena wax and wane, is needed via program announcements or conferences.

- Research on relapse prevention, desistance, and naturally occurring prevention is greatly needed.

D. Psychosocial Intervention

- We strongly urge that treatment studies move beyond assessing outcomes to focus more attention on the mechanisms or processes that influence those outcomes. These mechanisms may involve basic processes at different levels (e.g., level of neurotransmitters or stress hormones, information processing, learning, motivation, therapeutic alliance) and may be mediated by therapeutic approaches (e.g., practicing new behaviors, habituating to external events). Understanding the mediators and moderators of outcomes will be important in identifying the ingredients required for therapeutic change.

- We further recommend that treatment outcome studies assess outcomes beyond child symptom reduction to include functioning across various domains (e.g., school functioning, social interactions, family interactions, adaptive cognitions) to provide a more comprehensive picture of the benefits of psychosocial interventions.

- We recommend that NIMH promote a scientific agenda on the generalizability of psychosocial treatments by targeting funds toward the development or adaptation of psychosocial treatments that are implementable in real-world settings (e.g., schools and primary care), including the transportability of treatments with minority populations. Attention to the impact of development, culture, and context on the effectiveness of psychosocial treatments must be a priority. Such efforts will require the development of new methodologies to address the issue of increased heterogeneity in effectiveness trials, treatment fidelity (flexible vs. rigid adherence to treatment protocols), a clear definition of “treatment as usual,” and the use of appropriate comparison groups.

- We recommend that the psychosocial treatment program target the critical research gaps listed below:

- Comorbidity (e.g., substance abuse and depression, anxiety and depression, medical and psychiatric disorders)

- Potentially life-threatening conditions (e.g., eating disorders, suicide), bipolar disorders, anxiety spectrum disorders, autism, neglect, physical and sexual abuse, early-onset schizophrenia

- Gateway conditions of disorders (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder [ODD] as a gateway to conduct disorders, trauma as a gateway to post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], or ADHD as a gateway to ODD/conduct disorder/substance use) to divert onset of more serious disorders or impairments

- Parental mental illness and its influence on the prevention and treatment of child and adolescent mental disorders

- We recommend that priority be given to treatment modalities beyond cognitive behavioral therapy and behavior therapy (e.g., family therapy, Internet-based interventions), studies comparing psychosocial interventions for the same conditions (e.g., comparing combined treatment involving parent training and parent-child relationship therapy vs. child-focused interventions), and studies that address the issue of sequential psychosocial treatments and/or combined psychosocial and psychopharmacology treatments.

- We recommend that NIMH give funding priority to studies of common treatments and services available in the community (e.g., wraparound, treatment foster care, residential care, hospitalization), as they may provide a promising avenue for discoveries of new treatment approaches or strategies.

- Because so few studies have assessed the long-term outcomes of interventions (beyond 5 years), and because assessments of the cost-effectiveness as well as clinical and functional outcomes are needed to determine the benefits of treatment and impact on course of illness, we recommend that NIMH encourage long-term follow-up studies of treated and untreated populations.

E. Psychopharmacology

- We recommend expansion of the RUPPs to include the capacity for launching/conducting large simple trials to study issues such as comorbidity, dosing, and safety and efficacy of medication treatments across diverse cultural populations.

- We recommend increased research on the psychopharmacological management of serious mental illness (e.g., early-onset schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, severe depression) and pervasive developmental disorders (including autism and Tourette’s).

- We recommend that NIMH support the study of nonspecific symptoms that are often the targets of psychopharmacology management in children (e.g., aggression and sleep problems), but that have not been measured specifically. Better assessment measures to identify such symptoms need to be developed so that the symptoms can be assessed across disorders, and trials for these symptoms, independent of disorder diagnosis, may be considered.

- Disorder-based efficacy trials for new medications are currently being conducted for acute treatment, particularly for medications under patent protection. However, very few studies to examine long-term safety and efficacy are supported. We recommend that NIMH support such studies.

- We recommend the development of better study paradigms on psychopharmacology effectiveness, including augmentation strategies, multiple medication strategies, and the use of algorithmic treatments. Rational approaches to the management of comorbid disorders, medication side effects, and treatment resistance are needed.

- Studies examining reasons why patients do or do not follow treatment recommendations are needed. Further, studies are needed on the impact of the long-term use of medications, including their impact on psychosocial functioning.

- We recommend supporting basic and clinical neuroscience research on mechanisms underlying brain development and the biochemical and behavioral actions of psychotropic agents in animals and humans to increase understanding of drug actions in the developing brain and individual differences in treatment response (i.e., variability in optimal dose levels). Further, research on brain imaging to identify subtypes of diagnostic categories may have different treatment intervention implications.

- We recommend that the study of both the short- and long-term consequences (negative and positive) of pharmacological interventions associated with acute, recurrent, and chronic exposure to psychotropic agents on the developing brain be a priority for new NIMH initiatives.

F. Combined Interventions and Services

- We recommend the use of grant supplements to current service effectiveness projects to examine factors influencing the adaptability and sustainability of interventions (e.g., different roles of family in the research process, strategies for engaging families, and ways of increasing or maintaining treatment fidelity).

- We encourage careful attention to issues of defining, characterizing, and operationalizing current practice. Currently, researchers largely ignore usual practice because the variability within and across practice settings makes these processes extremely difficult and complex to measure. Yet, understanding intervention approaches developed in the field is important, as such approaches often reflect the needs of children and families and the constraints of personnel, as well as organizational and system limitations. Most of these studies will not be randomized trials because of the nature of routine practice.

- We recommend studies that examine how existing services (e.g., school-based, case management, mentoring, family support), combined treatments, and novel delivery mechanisms (e.g., Internet-based) can be used to augment clinical interventions to meet the significant needs of children with severe mental illness or those with multiple problems more successfully.

- We recommend studies on the impact of family engagement and choice regarding the acceptability of interventions.

- We recommend that a mechanism such as a B/START (Behavioral Science Track Award for Rapid Transition) be used to establish community collaboration prior to implementing research programs.

- We recommend that NIMH develop a national system or a series of regional systems to track the utilization and costs of child mental health services. The systematic tracking of broad indicators of utilization and costs, such as inpatient days, outpatient utilization by insurance status, and socioeconomic characteristics, would allow a more timely recognition of the effects of major changes in the health care system, including increasing or decreasing inequities. As part of these tracking systems, pharmacoeconomic studies are encouraged. Integration of data (service use and costs) from other settings likely to provide a substantial amount of services (e.g., the education, juvenile justice, and child welfare systems) not captured in the existing health databases is essential.

- New technologies will change care dramatically over the next decade. In addition, delivery of care is moving away from clinic-based models and toward models of patient-centered family care delivered in out-of-office settings, including on the Internet, in the home, in the school, in primary care and other settings. Because this trend is likely to continue, we recommend that studies of nontraditional delivery of services be encouraged and supported through program announcements or special funding initiatives.

G. Dissemination Research and System Improvement

- We recommend that investigators be strongly encouraged to conduct dissemination studies in public sector mental health sites, collaborating with other child-serving sectors. Because of the major activities of the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) in promoting systems of care through its Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, we strongly endorse the NIMH Program Announcement (PA-00-135), “Effectiveness, Practice, and Implementation in CMHS’ Children’s Service Sites.” This program announcement is sensitive to the need to disseminate evidence-based clinical practice to very high-risk youth receiving services in public sector programs. However, to facilitate meaningful research in these public sector sites, a major technical assistance effort will be necessary to bring together investigators and service sites.

- We recommend that priority be given to research on the factors that facilitate or impede the transportability or sustainability of evidence-based treatments. Factors identified may include extra-organizational factors (e.g., stakeholder involvement, triage system), organizational factors, practitioner behavior factors (e.g., attitudes and readiness to change), and family and child characteristics (e.g., attitudes, preferences, or co-occurring disorders) as they are related to dissemination and uptake of effective clinical services. Such factors may guide the development of incentives to optimize the use and sustainability of evidence-based treatments. Such research is especially needed in communities or populations where disparities in access to mental health care are prevalent, including minority communities and the uninsured.

- We recommend that NIMH consider the use of Small Business Innovation Research program funds for deployment, method/analysis development, or dissemination research to develop new commercial products and potentially expand the range, function, and effectiveness of therapeutic services.

- We support continued partnerships with other Federal agencies in order to capitalize on their dissemination arms. These agencies include those of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—CMHS/SAMHSA, AHRQ/HRSA, MCHB/HRSA, the Administration for Children and Families, and other NIH Institutes—the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Department of Education; and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Department of Justice, to carry forward research advances in both policy and practice arenas.

- A highly visible national dissemination effort is needed. We recommend the creation of a Dissemination Center. The research focus of this center would include dissemination and sustainability studies, with a special focus on understanding the validity of evidence-based treatments for minority populations. In order to conduct these studies, theoretical and empirical literature on organizational and practice change will need to be critically and creatively addressed, and different approaches to diffusion will need to be tested. Initial work by the center would be to identify experts in the change process from other fields and to utilize them in adopting or adapting the complex provision of mental health care services for targeted children and families.

IV. NIMH Oversight of Recommendations: Monitoring Progress

A. Ethical Issues

- Because of the difficult ethical issues surrounding studies of child and adolescent mental health and the paucity of scientific studies on informed consent, confidentiality, and risk assessment with which to guide investigators, we recommend that priority be given to these issues through workshops, program announcements, and special funding initiatives.

B. Governance and Monitoring of Recommendations

- We recommend that the Associate Director for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Research at NIMH report annually to the National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC) about the implementation of these recommendations. In particular, a report should be provided on changes in the scope of and funding for child and adolescent research.

- We recommend that special consideration be given to elevating funding priorities for child and adolescent grants that reflect the interdisciplinary linkages underscored and highlighted in this report. The objective of these initiatives is to create bridges among differing research traditions, and to do so well will require sustained support.

C. Administrative Oversight Within NIMH

- Because the NIMH Child and Adolescent Research Consortium (CARC) has been highly successful in setting research priorities that cross the divisional structure at NIMH and in encouraging creative initiatives to foster children’s mental health, we recommend that the NIMH CARC be retained and fully supported.

- To increase administrative capacity within NIMH, we recommend that consideration be given to retaining individual expert consultants, as needed, to provide advice to the NIMH director about research directions and priorities in child and adolescent mental health.

I. A Look Backward:

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Research

A. Historical Context

The first English book on pediatrics is considered to be “The Boke of Chyldren” by Thomas Phaire, published in 1544. Phaire included a lengthy list of “perilous diseases” of children, including, among other illnesses, “apostume of the brayne” (most likely meningitis), bad dreams, and colic. According to Neal Postman in “The Disappearance of Childhood” (1994), Phaire’s book heralded the notion of childhood itself, marking one of the first occasions when childhood as a concept was distinguished as a period of development separate from adulthood.

The concept of childhood mental illnesses, however, did not arise until the late 19th century, and they were typically not seen as unique to children or distinguishable from adult manifestations of mental illnesses until the early part of the 20th century. William Healy established the first child guidance clinic in the United States in 1909. Healy advocated for both the “team approach” and the “child’s own story” in treatment and research (Snodgrass, 1984). The first English-language text on child psychiatry was published in 1935 (Kanner, 1935; Sanua, 1990). Autism and ADHD (then known as hyperkinesis) were recognized as childhood disorders in the 1940’s and childhood depression in the 1950’s. In the 1970’s, during a WHO seminar on the classification of mental disorders for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the coding scheme for clinical syndromes in child psychiatry was first suggested. This first multiaxial scheme for children was developed and evaluated in 1975 (Rutter, Shaffer, & Shepherd, 1975) and formed the basis for subsequent classification and refinement in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association. The United States was required by international treaty to use the ICD for maintaining statistics, and so the DSM for the past three decades has used criteria similar to those used in the ICD.

The DSM is generally deemed to be an authoritative compendium of diagnostic categories for mental illness. It was not until the third edition of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) that child and adolescent mental disorders were assigned a separate and distinct section within that classification system. This edition of the DSM was widely read; by 1990 more than 2,300 scientific articles referred to it in title or abstract (Kirk & Kuchins, 1992). The DSM established boundaries over the domain of psychiatric classification and consequently controlled discourse about mental illness, structured research directions, and established the parameters of knowledge, including theoretical understanding, about mental illness.

The recognition that children and adolescents suffer from mental illnesses is thus a very recent phenomenon. The development of treatments, services, and preventive approaches to risk for these disorders is even more recent. However, in the past two decades, stemming in part from the rapid advances in psychopharmacology, in adaptations of adult psychosocial treatments for use with children, and the advent of community-based rather than institutionally based care, the knowledge base on treatments, services, and prevention programs has greatly expanded. In addition, tremendous progress has occurred in mapping and cloning genes for diseases that follow Mendelian patterns in families. However, the discovery of the genes that influence susceptibility to more complex diseases such as neurobehavioral disorders has proceeded slowly. The lack of one-to-one correspondence between genotype and phenotype, and the etiological complexity of common mental disorders such as ADHD, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and schizophrenia, present considerable challenges for researchers.

In order to harness the avalanche of genomic information being generated from new and evolving molecular technologies, innovative quantitative methods are being developed to foster genome-wide analyses. With these new methods under development to map genes for complex diseases, the field of genetics shows promise of providing insights into the biological underpinnings of these diseases, which will advance current diagnostic, prevention, and treatment efforts. Such insights are critical to understanding how genes contribute to vulnerability or resistance, affect the severity or course of illness, and interact with environmental factors that modify their expression or course. These advances are especially critical for children with neurobehavioral disorders because early onset of such diseases tends to be associated with a greater genetic load. With the growing research focused on the genetic control of the developing brain structure and system, as well as the powerful technology that continues to evolve and provide access to the developing brain, unprecedented opportunities for understanding the etiology of mental disorders, and hence ways to divert adverse developmental trajectories, have been created.

In the past 10 years, families of children with mental illnesses and consumers have taken a much more active role in treatment delivery and service planning. The importance of attending to and engaging families in every aspect of mental health services has become the sine qua non of treatment and care plans. Not only does such engagement represent the only defensible moral platform from which to consider the needs of families and children, it also represents recognition of the fact that solutions to child and adolescent mental illness require the partnership of professionals, families, scientists, and youth themselves.

Treatments for childhood disorders such as conduct problems, anxiety disorders, adolescent depression, OCD, and ADHD have been the primary targets of recent study. In the past 2 years, five reviews of treatment and service studies have been published, summarizing hundreds of studies, most conducted since 1980 (Burns, Hoagwood, & Mrazek, 1999; Child Mental Health Foundations and Agencies Network, 2000; Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1999; Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 1998; Weisz & Jensen, 1999). These reviews span a host of interventions, including preventive approaches for behavioral problems that may emerge into full-blown disorders, medication and behavioral treatments for attention deficit disorders, and services for multiproblem children. The availability of a range of treatments, prevention programs, and services for children with functional impairments is thus a new phenomenon. It suggests that the situation for families whose children are at risk, or who have developed mental illness, is not hopeless. A scientifically defensible corpus of treatments, services, and preventive interventions now exists.

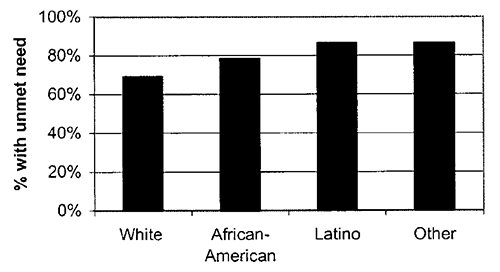

Yet, despite this progress, the burden of childhood mental health problems is not lessening. Report after report cite the fact that childhood mental health problems and illnesses are common, are on the rise, and impose serious burdens on children and families alike (Achenbach & Howell, 1993; Burns et al., 1995; Knitzer, 1982; Murray & Lopez, 1996; Roberts, Attkisson, & Rosenblatt, 1998; National Advisory Mental Health Council, 1990; Shaffer et al., 1996; U.S. Public Health Service, 1999). The level of unmet needs for services is as high as ever, despite two decades of treatment development and mental health service delivery (Burns et al., 1995; Sturm, Ringel, Bao, Stein, Kapur, Zhang, & Zeng et al., in press; also, see appendix A). There are probably a number of reasons why the burden has not lightened.

Stigma

The reasons for the continued and pervasive level of unaddressed mental health needs among young people in this country are many. One perpetual impediment has been the existence of attitudinal bias or stigma toward mental illness. Mental illnesses have not been accorded the same level of credibility as other health disabilities, yet there is no scientific justification for this difference. Stigma continues to affect families whose children experience mental illness by creating a culture of suspicion, discrimination, fear of mental health problems, blaming the parents, and very real concerns about treatment confidentiality and restriction of insurance coverage.

Fragmentation of Social Institutions

The social institutions primarily responsible for providing mental health support—schools, mental health clinics, and hospitals—remain fragmented and entrenched in models of service delivery that do not match child and family realities. Specialty mental health treatments still tend to be delivered in offices rather than in homes, schools, or health settings. Children with unrecognized mental health problems are still sent to out-of-home placements, often miles away from their families, rather than being treated in communities. The lack of availability and infrastructure support for treatments, prevention programs, and services is as high as it was in the early 1980’s (U.S. Public Health Service, 2000).

Health Disparities

The disparities between minority children and the majority population in health status and access to care have been a source of significant concern (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1994). Mental disorders appear to have equivalent incidence and prevalence across majority and minority populations. However, they may exert a disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minority groups (NIMH, 2001). This disproportion is evidenced by uneven access to services, poorer treatment, and worse mental health outcomes among minority populations. According to evidence recently presented at the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health (U.S. Public Health Service, 2000), this finding holds for both children and adolescents. Among this population, unmet need for specialty mental health care is high, and there are substantial ethnic disparities in access to such care (Wells, unpublished data). Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences influence the expression and identification of the need for services (e.g., caregiver expectations), quality of care (e.g., whether or not children receive medication), referral bias or access to appropriate care (e.g., referral to school services or specialty care settings vs. justice or welfare systems for similar problems), the diagnostic process (e.g., lack of culturally competent providers), and hence subsequent care and poorer health outcomes. Similarly, children whose parents are in chronic poverty or who have experienced severe economic losses are at a greater risk for anxiety, depression, and antisocial behaviors (McLeod & Shanahan, 1996; Samaan, 2000).

Resources

Many treatments and services children and their families receive have not been examined or evaluated. A significant proportion of the mental health dollar for children continues to go to treatments and services that have been shown to be largely ineffective or have not been shown to be effective. The question of how to redirect costly residential, hospital, and outpatient (when not evidence-based) resources into more effective care is both a research and a policy issue. The challenge of implementing science-based treatments and services rests not only on good dissemination but also on the realignment of resources to ensure that children and families in need receive the most appropriate care in a timely manner. This requires the research community to partner with families, providers, and other mental health stakeholders and policymakers to realign current resources to ensure that the science base on treatments and services is usable, implementable, disseminated, and sustained in the communities where children live.

Evidence-based Treatments

In the field of children’s mental health science and service deliver, the term evidence-based refers to a body of knowledge, obtained through carefully implemented scientific methods, about the prevalence, incidence, or risk for mental disordres or about the impact of treatments or services on mental health problems.

It is a shorthand term denoting the quality, robutsness, and validity of the scientific evidence that can be brought to bear on questions of etiology, distribution, or risk for disorders or on outcomes of care for children with mental health problems.

Research Gaps