Bridging Science and Service: A Report by the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup

Table of Contents

- Preface

- Executive Summary

- Treatment and Services Research: An Alliance for Progress

- Enhancing the Public Health Value of Mental Health Research

- Introduction

- Key Perspectives and Priority Setting

- Issue: Integrating Public Health Benefit and Scientific Merit to Establish a Research Agenda

- Issue: Research-Based Consensus Development

- Issue: Creating an Infrastructure for Monitoring Public Mental Health and Assessing the Impact of Research Summary

- Making Connections

- Methods Development and Innovation

- Introduction

- Issue: Incorporating Measures of Costs Associated with Interventions

- Issue: Tailoring Interventions to Communities

- Issue: Tailoring Interventions to Distinct Subgroups

- Issue: Considering Treatment Preferences and Decision Making

- Issue: Confidence in Drawing Conclusions from Findings

- Issue: Assessing External and Internal Validity

- Issue: Fostering Innovative Methods

- NIMH’s Leadership Role in Program Development, Review, and Administrative Activities

- Introduction

- Program Development: Selecting or Creating an Appropriate Funding Mechanism

- Issue: Mechanisms for Training

- Issue: Mechanisms for Creating Collaborative Research at Provider Sites

- Issue: Requirements for Meeting the Broader Scope of Public Health Research

- Issue: Review Criteria

- Issue: Expediting Administrative Decisions

- Review Considerations

- Issue: Review Structure

- Issue: Ensuring Expertise in Peer Review

- Issue: Conflicts of Interest

- Issue: Role of the Scientific Review Administrator (SRA)

- Administration

- References

- Appendix A: National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC)

- Appendix B: NAMHC Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup

- Appendix C: Roster of Consultants

Preface

An urgent task before the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) is to generate information that, properly used, will better enable people with mental illnesses to receive optimal care. Such information is needed by mental health care providers, general health care personnel, service systems administrators, policymakers, and, importantly, patients and their families. Through research we continue to develop and refine an array of safe and efficacious interventions, yet more emphasis must be devoted to translating the yield of basic and clinical research into effective treatments for patients encountered in non-research settings. More attention must be paid, also, to designing treatment delivery systems and policies that facilitate provision of optimal care. Persons with mental disorders and their care providers are entitled to the same high quality of research-based information upon which to make treatment and service decisions as persons with heart disease, cancer, or other general medical conditions.

The NIMH in recent years has targeted resources to increase substantially the breadth and depth of the mental health services research field. Our growing services research capacity is an important counterpoint to our strong basic research portfolio in neuroscience, molecular biology, and basic behavioral research. These two arenas—basic science and service systems research—bracket a third component of the NIMH research program: clinical research and, particularly, treatment trials. The pace of advance in basic and clinically inspired research, and the extent of change in service systems and the questions posed by the various types of patients, providers, and settings demand a thorough reappraisal of the manner in which we explore and evaluate clinical innovations and move them into the hands of service providers.

Recognizing this need, the NIMH leadership requested the National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC) to establish a Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup that would undertake an in-depth review of the pertinent issues. Under the insightful and energetic leadership of A. John Rush, M.D., a core group of the Nation’s most distinguished treatment and services researchers met over the course of a year, among themselves, with outside consultants, and with members of the NIMH and other Federal officials. The outcome of these deliberations is seen in the report that follows, and specifically in the recommendations made for modernizing and revitalizing our approaches to treatment and services research.

No less critical than the calls for action at institutional levels is the open, inviting tone of the report. Unlike laboratory research, relevant treatment and services research demand the broadest possible levels of interest and participation on the part of the clinical community, policymakers, and consumers of services. Special efforts were made by the Workgroup—and will be continued by the NIMH—to solicit the needed breadth of involvement. In conjunction with the completion of the work of the Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup, for example, we were pleased to announce that NIMH is establishing a new Office of Communications and Public Liaison, one strategy for broadening the interface between our scientific programs and the many “stakeholders” in our research. We will continue to seek more innovative ways of achieving productive interactions with individuals and organizations who have contributions to make to our research planning and specific projects. A user-friendly NIMH home page on the World Wide Web offers one approach; active solicitation of committed and creative individuals to serve as scientific and public reviewers on the Institute’s advisory committees or as members of local Institutional Review Boards offers another.

We are pleased to make this document available to all interested parties and we welcome your comments, including suggestions for additional steps we might take to enhance the relevance of clinical and services research and the power of such research to put vitally needed information in the hands of those who will use it to the benefit of Americans with mental illnesses.

Steven E. Hyman, M.D.

Director, National Institute of Mental Health

Executive Summary

Historically, the vulnerability and suffering of persons who live with disabling mental illnesses too often were ignored or misunderstood by much of society. Yet over the past half century, the people of the United States, through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), have supported medical, neuroscientific, and behavioral research on mental illnesses consistently and generously. With that support, and that of others (e.g. foundations, industry, and other Federal agencies), a remarkable scientific effort has demonstrated convincingly that mental illnesses affect a specific organ-the brain-and that in the vast majority of instances, mental illnesses can be treated successfully using an array of specific interventions.

Researchers, policymakers, health care providers, and most critically, individuals with mental illnesses and their families today recognize that translating the remarkable breakthroughs into procedures and policies of everyday clinical practice is an urgent, essential, and achievable task. It is a challenge that has profound implications for the quality of the lives of Americans with mental illnesses and for the health of the Nation.

The Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup of the National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC) was charged by the Director of the NIMH to advise the Council on strategies for increasing the relevance, speeding the development, and facilitating the utilization of research-based treatment and service interventions for mental illnesses into both routine clinical practice and policies guiding our local and national mental health service systems.

The Workgroup reviewed the NIMH research portfolio that extends from academic research settings to large, State-wide service systems, to the moving target of “front-line” clinical care. The review made vividly clear the need for mutually enriching interaction between research and both practice and service systems. In addition, the Workgroup consulted with representatives from advocacy groups, insurers, public and private purchasers, researchers, and State and Federal policymakers. Although these perspectives were not all concordant, they did highlight the fields’ capacity to enhance the delivery of treatment and services available to individuals with mental illnesses.

Toward this end, the Workgroup shaped an action plan with 49 recommendations for fulfilling the Nation’s commitment to individuals with mental illnesses. This action plan is structured by the goals of informed priority setting, using a dynamic and rapidly growing knowledge base, as well as methodological innovation, and administrative and infrastructure enhancements. The specific recommendations follow.

- Increase the usefulness of NIMH research for individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians, purchasers, and policymakers through informed priority setting.

- NIMH should establish an ongoing priority-setting process that integrates the perspectives of patients/consumers, providers, purchasers, researchers, and policymakers in determining long-term initiatives and responding to scientific opportunities to improve the relevance of mental health intervention research.

- NIMH should renew its role in providing a forum for focusing the key perspectives in the mental health research enterprise to develop clear and productive lines of bi-directional communication.

- NIMH should support the synthesis of available information on mental illnesses, their treatment, and service needs to enhance priority-setting meetings.

- NIMH should routinely organize consensus development conferences on specific mental illnesses to synthesize the research findings.

- NIMH should conduct these activities in conjunction with appropriate partners, such as the Center for Mental Health Services and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, to provide the necessary integration for the Federal effort.

- NIMH should collaborate with Federal, State, and private agencies to establish a mechanism to monitor the value (as defined by an equation of quality, access, and cost) of mental health care delivered across the Nation and the impact of policies on practice and service systems.

- Selectively expand the NIMH portfolio in the domains of efficacy, effectiveness, practice, and service systems research to foster integration across these fields and to expedite the implementation of research-based practices and policies.

- NIMH should augment its efficacy portfolio with research that assesses the generalizability of interventions across diagnostic complexities (e.g., comorbidity or chronicity), as well as individual, social, and demographic factors.

- NIMH should enrich its efficacy portfolio with trials that measure change in terms of both symptoms and function over a meaningful period of time.

- NIMH should incorporate rehabilitation into its intervention portfolio.

- Research should be encouraged that better characterizes promising interventions, patient/consumer populations, ongoing treatments, and service settings.

- NIMH should expand its effort in clinical epidemiology through workshops and through developing research addressing the issues in the epidemiology of care.

- NIMH should expand its effort in generating research to inform and evaluate treatment guidelines in conjunction with other Federal agencies.

- NIMH should review the current measures of functional status and support tests of which measures or items are reliable, valid, and have clinical utility.

- NIMH should expand its research portfolio to include the interface between the architecture of services (i.e., the structure, organization, and financing of services) and its effects on the quality of care and clinical outcomes (symptoms and functioning).

- NIMH should support targeted research on how to synthesize and incorporate existing knowledge into clinical practice better, with particular emphasis on understanding factors and mechanisms involved in changing practice and systems of care.

- NIMH should encourage and sponsor more research that links service systems changes with quality of care and other clinical indicators of patient/consumer status.

- NIMH should sponsor validation studies of assessment tools designed to measure the quality of health care across systems of care to assist policymakers and patients/consumers with decision making.

- NIMH should encourage the use of existing databases for understanding service systems.

- Identify research innovations in design, methods, and measurement to facilitate the translation of new information from bench to trial to practice.

- NIMH should improve measures and analysis of costs in intervention studies, with special attention to successful examples from general medicine.

- Large intervention studies should include a cost-effectiveness component that uses the best methodology available.

- Approaches to conceptualize and assess key characteristics of intervention settings should be developed, as should models for understanding the effects of these characteristics on outcomes.

- NIMH should encourage the development and evaluation of key research measures for assessing “usual care” and develop analytic methods to adjust for variation in components of usual care.

- NIMH should promote development of innovative sampling strategies for inclusion of underrepresented groups and sufficiently large intervention studies to incorporate representative community populations.

- NIMH should encourage the development of methods to study and incorporate clinician and patient/consumer decision-making processes into intervention research.

- NIMH should support research to identify common practices believed to be helpful and bring them under research scrutiny, that is, ascertain what is going on in the practice community and determine how much of that is beneficial.

- NIMH should encourage the improvement of methods for both evaluating clinician implementation and patient/consumer adherence to treatment recommendations and estimating the consequences of these variations on the effectiveness of treatment.

- NIMH should explore new methods for analysis of data from studies that incorporate innovative combinations of research designs.

- NIMH should encourage development of methods to explicitly evaluate trade-offs in alternative design features that differ in their implications for internal and external validity.

- NIMH should convene a methods workshop to identify options for advancing intervention and service systems research. The results of this workshop should be debated broadly and options tested in appropriate follow-up activities.

- Strengthen NIMH’s leadership and administrative activities to provide the infrastructure to achieve the goals stated above in a timely manner.

- NIMH should develop additional training and career development programs that offer hands-on experience in diverse research settings in order to provide researchers with an enriched training experience.

- NIMH should revise and renew program announcements (PAs) in the spirit of the Public-Academic Liaison (PAL) Program to maintain and promote existing partnerships between academic researchers and public care systems, health plans, both carve-outs and health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and employers providing health benefits and their representative groups.

- NIMH research centers, which demonstrate great potential to secure partnerships with service delivery systems and to utilize these systems to conduct intervention research, should be supplemented to develop, implement, and sustain such partnerships.

- NIMH should issue a request for applications (RFA) or PA to encourage secondary analyses of service systems data and to establish accessible formats for such data to maximize the use of databases in practice settings.

- NIMH should stimulate new alliances by providing developmental funds to establish shared research resources such as data banks, staff time, consultant time, etc.

- NIMH should commit resources to identify, describe, and disseminate models of successful partnerships.

- NIMH should consider contracts as a mechanism for supporting clearly articulated research needs and deliverables.

- The importance of public health relevance should be specifically added to the review criteria in new PAs, RFAs, and requests for proposals in the relevant areas to emphasize its significance for applicants and reviewers.

- NIMH should develop a mechanism for responding to unique, but fleeting research opportunities with great public mental health significance.

- NIMH is asked to work with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to encourage timely joint funding decisions for comorbid substance abuse and mental illness research.

- Efficacy, effectiveness, practice, and service systems research applications should remain at the Institute for review, and the clinical and services study sections reconstituted, including an appropriate mix of expertise among reviewers.

- NIMH staff should attend carefully to planned evaluations of the Center for Scientific Review neurosciences and AIDS review mergers, as well as the upcoming behavioral sciences merger, to enhance future restructurings of NIMH review.

- NIMH should explore shared review opportunities with NIAAA and NIDA to enhance the review of applications on comorbid substance abuse and mental illness applications.

- Review panels should have patients/consumers, providers, or policymakers as members to ensure expertise on the utility of research findings in intervention research.

- NIMH staff should explore how other institutes deal with conflicts of interest and consult with the National Institutes of Health on revising and implementing the conflict-of-interest rules for intervention research.

- Scientific Review Administrators (SRAs) should strive to maintain a link between special emphasis panels and the regular review committees through a subset of the regular reviewers and, whenever possible, the special emphasis panels should be arranged to precede or follow immediately the regular review meeting to facilitate the use of committee members and their scoring standards.

- SRAs and panel chairs should actively consider when scientific breakthroughs require a substantive update for the review panel. The SRA and chair may convene a workshop to brief the committee.

- NIMH should make judicious use of its ability to make funding decisions out of percentile order to achieve its programming objectives.

- Grant budgets must be based upon providing essential support as determined by review groups and NIMH program staff for achieving research’s scientific and public health aims.

- NIMH should increase its use of administrative and competitive supplements to provide additional funds and time to researchers to test the generalizability of their findings or to disseminate important research findings.

Chapter 1

Treatment and Services Research: An Alliance for Progress

Introduction

Recent decades have brought remarkable advances in our abilities to diagnose and treat mental illnesses. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has played a pivotal role in supporting the research that has made it possible to enhance, often dramatically, the lives of persons with these illnesses. Research has contributed to the quality and breadth of treatments available and has reduced significantly the stigma attached to mental illnesses. Scientific and clinical advances have helped the public to understand that mental illnesses are treatable medical conditions. Ongoing research is elucidating the complex interplay between brain and behavior and forecasts even more significant developments in treatment and prevention strategies and in public understanding.

The scientific grounds for a sense of accomplishment and optimism are firm. Still, satisfaction with what is known about mental illnesses and their treatments must be tempered. Mental health service settings and systems of care are evolving rapidly, often outpacing the rate at which new knowledge enters clinical practice. Also, the economics of mental health services delivery is being transformed. And, importantly, individuals with mental illnesses and their families have achieved a strong voice in helping to set priorities and processes of care.

Amidst these changes, many people are unable to obtain, for themselves or for one close to them, appropriate, state-of-the-art treatment for a mental illness. All too often, clinical practices and service system innovations that are validated by research are not fully adopted in treatment settings and service systems for individuals with mental illnesses. The substantial disparity between what is known through research and what is actually provided in routine care is not limited to mental illnesses. Significant gaps between what is known and what is practiced have been documented in other areas of medicine as well, including cancer (Cronin et al. 1998), diabetes (McClellan et al. 1997), and cardiac care (Howard and Duncan 1997).

Rapid changes across health care, juxtaposed against continuous scientific advances, raise urgent questions for all parties involved in the Nation’s mental health:

- For patients/consumers and their families, the questions are straightforward. What treatments will help? What treatments are best? How can we be sure that a specific treatment is both appropriate and of high quality? How can we afford to pay for the treatment?

- Clinicians have different, but related questions. What is the best treatment for this patient/consumer? What treatment should be recommended next if the first is unsuccessful? What are the clinical and financial barriers to applying different approaches to care?

- Health care administrators must address questions at a different level. For example, what types and levels of care are appropriate for specific patient/consumer groups? What resources are needed to provide such care, and how should they be delivered and integrated?

- Policymakers, purchasers, and insurers must make important decisions regarding access to and coverage for patient/consumer care. For them, the questions are no less urgent. What will it cost to pay for effective treatment? What will it cost, in terms of protracted disability and related costs, not to pay for treatment? What delivery system and financial incentives will provide optimal cost-effectiveness of care? How do purchasers receive value for their investment?

The NIMH, along with other Federal agencies, is responsible for the research that is generating answers to these questions. In 1991, the Institute issued Caring for People with Severe Mental Disorders: A National Plan of Research to Improve Services. Prepared under the auspices of the National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAMHC), this benchmark report was one of the factors that invigorated the field of mental health services research in recent years. Since 1991, NIMH support for treatment and services research has increased from $82 million to $170 million in fiscal year (FY) 1997. Years of accelerated growth now have made it timely and important to examine the Institute’s progress and, where necessary, to adjust the Institute’s efforts in light of rapidly evolving science, systems of health care, and technologies for information dissemination.

The Clinical Treatment and Services Research Group

In September 1997, Dr. Steven E. Hyman, Director of NIMH and Chair of the NAMHC (see Appendix A for roster), convened a workgroup of researchers, policymakers, and mental health advocates to advise the Council on the array of issues that are the domain of clinical treatment and mental health services research. The director’s charge to the NAMHC Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup (see Appendix B for roster) was to speed the development and routine utilization of research-based treatment and service interventions in daily practice. Dr. Hyman asked the Workgroup to consider factors that influence the development, translation, and implementation of research findings into practice. He urged the Workgroup to consider how to build most effectively on the experiences of other institutes within the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He also encouraged development of strategies to improve the synergy of the NIMH’s relationships with patients/consumers and families, managed care organizations (MCOs), public and private purchasers, and other major “stakeholders” in the mental health system.

Definitions

As the Workgroup began its deliberations, members had to come to terms with the lexicons of many different research fields. Although the Workgroup’s name indicates a focus on treatment and services research, these two terms meant different things to different members of the Workgroup. Other terms used in the separate literatures also were ambiguous, so the Workgroup gradually developed its own working lexicon. These definitions are provided for clarification and have the additional benefit of surveying the many exciting areas that mental health researchers are exploring. These distinct groupings are provided for discussion purposes, because as discussed later in this report, these areas do or should overlap.

Efficacy Research

The purpose of efficacy research is to examine whether a particular intervention has a specific, measurable effect and also to address questions concerning the safety, feasibility, side effects, and appropriate dose levels. As a consequence, the classic efficacy study is a clinical trial in which an experimental treatment is compared to a control treatment that can be a standard treatment and/or a placebo. Because the chief concern is to detect any treatment effect, researchers try to eliminate or hold constant any factors that may obscure this effect. For instance, to reduce the influence of researchers’ and participants’ expectancies on the assessment of effect, clinical efficacy trials are often double-blind. This means that both the research staff and the participant do not know who is getting the experimental treatment and who is getting the control treatment. Also, efficacy trials usually employ highly restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting participants. This is because the more similar the participants are, the easier it is to detect the effect of a treatment as well as its side effects. Complicating factors such as co-occurring substance abuse or other illnesses are typical exclusionary criteria. Despite these criteria, not all factors can be anticipated or controlled. For this reason, efficacy trials typically randomly assign participants to the experimental or control condition. The goal is to be sure that condition assignment is based on “the luck of the draw” rather than an undetected confounding factor.

In addition to double-blind, randomized, clinical trials, efficacy research typically has other common features: (1) study settings are highly controlled to ensure optimal treatment delivery (e.g., with clinicians who follow a strict set of procedures in providing the experimental and the control treatment); (2) treatment is provided without cost to participants; (3) the “effect” is usually defined by shorter-term clinical outcomes such as symptom reduction after a month or two rather than longer-term outcomes such as the ability to function at home or work over months to years; and (4) economic variables such as costs or health care utilization are not typically measured.

Effectiveness Research

The principal aim of effectiveness research is to identify whether efficacious treatments can have a measurable, beneficial effect when implemented across broad populations and in other service settings. For instance, any person seeking help with a particular mental illness, regardless of other co-occurring conditions or the duration of the illness, might be eligible. Treatments are administered by clinicians who have not necessarily been specially trained in the research protocol; patients/consumers and clinicians exercise choices over treatments; and the frequency and duration of visits, how and when outcomes are gauged, and the use of adjunctive services are dictated by local practice patterns or administrative policies. Effectiveness studies can be randomized controlled trials, but as in some types of efficacy work, blinding of the participants and/or researchers is not always possible. Traditionally, effectiveness studies focus on more broadly defined outcome measures such as disability and quality of life, and have placed less emphasis on detailed evaluation of clinical status. With the increasing emphasis on cost of care and efficient service delivery, many effectiveness studies now incorporate analyses of the cost-effectiveness of various mental health interventions when compared to care as usual or an alternative treatment. Of course, design elements for effectiveness trials can include random assignment and double-blinding, as discussed under efficacy.

Practice Research

Practice research examines how and which treatments or services are provided to individuals within service systems and evaluates how to improve treatment or service delivery. The aim is not so much to isolate or generalize the effect of an intervention, but to examine variations in care and ways to disseminate and implement research-based treatments. Although some studies may have randomized designs, currently most are observational. An emergent field, practice research is built on and encompasses at least three established areas of research inquiry:

- Clinical epidemiology represents a broad field that addresses what happens to people with illnesses who are seen by providers of clinical care. Studies use traditional epidemiological methods and are conducted in groups that are usually defined by illness or symptom or by a diagnostic procedure or treatment given for the illness or symptom. Thus, it includes studies of the natural history of an illness, studies of diagnostic and screening tests, and observational and experimental studies of interventions delivered to people with illnesses or symptoms.

- Quality of care research is concerned with defining and describing the care received in clinical settings and establishing and testing standards for quality of care. Areas of study include processes and outcomes of care; research on the structure of health organizations as it pertains to processes and outcomes; and the relationship among structures, processes, and outcomes. Components also may include research on treatment guidelines and clinical decision making. Considerations of economic impact in decisions about use of medical technologies and pharmaceuticals are important factors in this process.

- Dissemination research evaluates methods by which appropriate interventions are introduced and adopted in clinical practice, including factors that inhibit or facilitate such adoption. This research includes studying mechanisms to change clinician or patient/consumer behaviors, and to improve the delivery of clinical care. Quality improvement studies and practice guideline dissemination evaluations are currently main components of dissemination research. A relatively new field of research in mental health, dissemination research study designs may be either observational or randomized, depending on the nature of the question asked.

Service Systems Research

Service systems research addresses large-scale organizational, financing, and policy questions. This includes the cost of various care options to an entire system; the use of incentives to promote optimal access to care; the effect of legislation, regulation, and other public policies on the organization and delivery of services; and the effect that changes in a system (e.g., cost-shifting) have on the delivery of services. At the interface of service systems research and other areas of practice and treatment research are studies that integrate these different levels of inquiry (e.g., studies of how variations in service system characteristics affect quality of care). Studies of how treatment effects differ, in the context of different systems, integrate effectiveness and service systems research. Cost-effectiveness analysis has a very important role in evaluating various forms of treatment delivery systems. Service systems research study designs may incorporate elements of efficacy and effectiveness research.

Integration of Research Areas

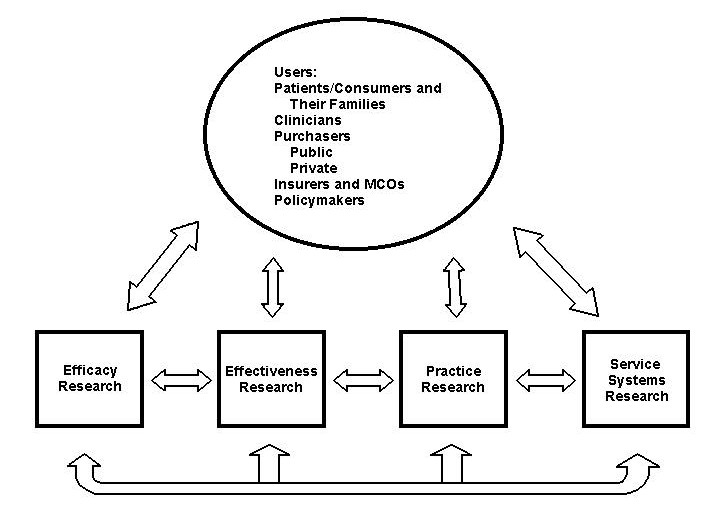

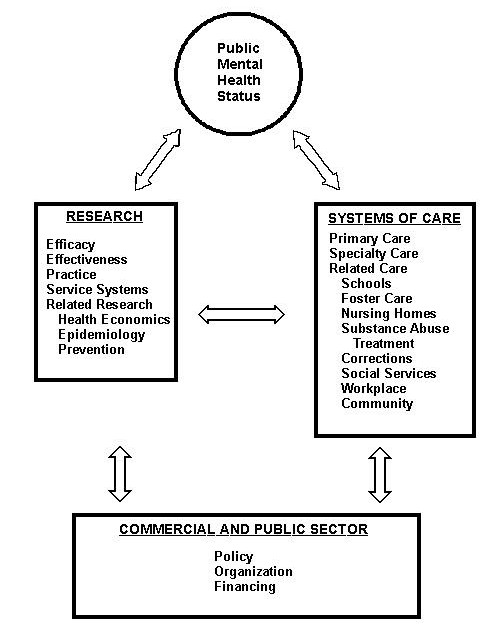

In an effort to bridge the existing divisions between the domains of efficacy, effectiveness, practice, and service systems research, the Workgroup developed a model that took into account these four types of research and the potential users of research (i.e., patients/consumers and families, clinicians, public and private purchasers, insurers and MCOs, and policymakers). This model (see Figure 1) demonstrates the interconnectedness of these domains, which are commonly, but inappropriately, viewed as discrete or linear.

Figure 1: Relationships Among Research Domains and Users of Findings

Treatments do not occur in isolation from patients/consumers, clinicians, and service setting factors. As research findings are made available to “end-users,” investigators in all four domains should consult with end-users to identify the next generation of research questions. Treatments are always administered in a context, and it is that emphasis on context that marks an important change in the treatment research paradigm. Further, a service system must have a strong method for understanding the clinical nature of an individual’s illness and functional status for the most appropriate provision of care. Accordingly, the four areas must be mutually informative, each building on the understanding provided by the other and addressing pressing public mental health concerns.

The model emphasizes the need for interaction across these domains of study and between research results and users of the research. Further, there are important cross- cutting areas of research such as health economics, epidemiology, and prevention. As a case in point, treatments designed without attention to costs may generate interventions that are only unaffordable and therefore impossible to implement. Economic studies are best focused on questions that arise regarding current interventions or those under consideration for implementation, ideally with these latter interventions being evidenced-based.

Status of the NIMH Extramural Research Program

The Workgroup conducted a comprehensive review of all NIMH-supported treatment and services research. Aims of this review were to identify gaps in the research portfolio, ascertain how to develop needed knowledge more effectively, and how to use available knowledge most efficiently and appropriately (i.e., how to foster awareness, acceptance, and use of new knowledge by practitioners and health care systems).

Within the NIMH, primary responsibility for efficacy, effectiveness, practice, and service systems research is assigned to three branches within the Division of Services and Intervention Research.

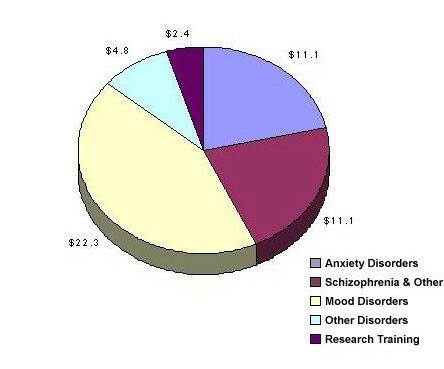

The Adult and Geriatric Treatment and Preventive Intervention Research Branch had a treatment research portfolio in FY 1997 that included grants and clinical trials contracts supported for a total of $51.7 million, including research training and career development (see Figure 2). The majority of the grants focus on treatment including mood disorders, principally major depressive disorder ($22.3M), schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders ($11.1M), a broad spectrum of anxiety disorders ($11.1M), and dysregulation disorders (principally eating and sleep disorders) account for the remainder ($4.8M). Pharmacology, psychotherapy, somatic treatments, and combination strategies are all represented. Treatment grants in the Branch portfolio at present are largely short-term efficacy trials with highly selected populations and outcomes focused on symptomatology.

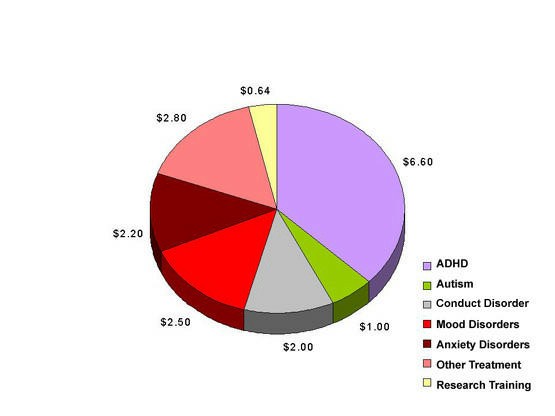

In the Child and Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Intervention Research Branch, the treatment research portfolio for FY 1997 included grants and contracts for a total of $17.7 million, including research training and career development (see Figure 3). This Branch focuses on clinical trials of treatments or preventive interventions for children and adolescents. Slightly more than half of the Branch’s funding is devoted to preventive interventions (not represented in this figure). Treatment areas receiving the most funding in FY 1997 were attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder for treatment interventions ($6.6M), autism treatment ($1M), conduct disorder treatment ($2M), mood disorders treatment ($2.5M), anxiety disorders treatment ($2.2M), and other treatment for $2.8M.

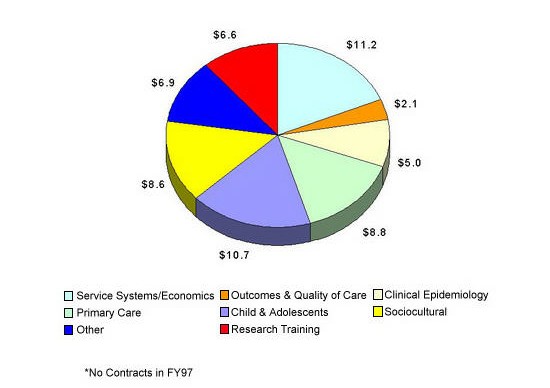

The Services Research and Clinical Epidemiology Branch had a research portfolio in FY 1997, including research training, for a total of $59.9 million (see Figure 4). The focus of this Branch’s funding is on access to care, structure and organization of care, process of care, outcomes, and financing and costs of treatment. Supported research areas included service systems and economics ($11.2M), primary care ($8.8M), children and adolescents ($10.7M), sociocultural ($8.6M), clinical epidemiology ($5.0M), outcomes and quality of care ($2.1M), research training ($6.6M), and the remaining ($6.9M) included a small portfolio of methodological research and other portfolios.

Figure 2: Adult and Geriatric Treatment and Preventive Intervention Research Branch, DSIR Treatment Grants and Contracts Fiscal Year 1997 – Total $51.7 million

Figure 3: Child and Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Intervention Research Branch, DSIR Treatment Grants and Contracts Fiscal Year 1997 – Total $17.7 million

Figure 4: Services Research and Clinical Epidemiology Branch Fiscal Year 1997 Services Grants* – Total $59.9 million

Defining the Issues

In addition to reviewing the Institute’s portfolio, the Workgroup sought input from a wide array of perspectives with which it evaluated the Institute’s activities and future needs. Workgroup members conferred with staff of NIMH and other Federal agencies. Patients/consumers and family groups, providers, public and private purchasers, and policymakers also were consulted (see Appendix C for roster).

The Workgroup took the innovative approach of inviting the participation of all interested parties and encouraging discussion. For example, the Workgroup opened a web site on the NIMH home page to post summaries of its activities and solicit comments from the public. Workgroup members held open discussions at various professional meetings to engage the research field. Further, NIMH staff attended Workgroup meetings and were encouraged to implement, in a timely manner, recommendations endorsed during the public Council updates rather than wait for the Workgroup’s final report. The rapid adoption of the Workgroup’s interim suggestions attests to the speed with which NIMH and NAMHC seek to provide more meaningful research findings. While other ideas require further discussion and a sustained commitment on the part of NIMH, stylistically, the Workgroup hoped to set a new tone for the Institute in its planning process. The need for open dialogue with users of research findings in an ongoing, intensive, priority-setting process at the NIMH is a recurring theme in this report.

Given the breadth of issues to be considered in developing an action plan, the Workgroup agreed upon four domains for developing strategic recommendations. Subgroups were formed to focus on each:

- Increase the usefulness of NIMH research for individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians, purchasers, and policymakers through informed priority setting.

- Selectively expand the NIMH portfolio in the domains of efficacy, effectiveness, practice, and service systems research to foster integration across these fields and to expedite the implementation of research-based practices and policies.

- Identify research innovations in design, methods, and measurement to facilitate the translation of new information from bench to trial to practice.

- Strengthen NIMH’s leadership and administrative activities to provide the infrastructure to achieve the goals stated above in a timely manner.

Each subgroup generated issues and recommendations, which were subsequently debated by the entire Workgroup. The Workgroup then met to shape a report that would reflect the diversity of perspectives and constructive ideas provided by the individuals and groups who had been consulted. The Workgroup believes that achieving these goals would position NIMH to fund high quality research to address urgent public health concerns. The Workgroup’s recommendations to foster each goal are described in the following chapters.

Chapter 2

Enhancing the Public Health Value of Mental Health Research

Introduction

A key measure of the value of research is its beneficial impact on society and, more precisely for NIMH-funded research, on public mental health.

This report defines public mental health as the number of mental health conditions of individual, clinical, and societal significance in the general population. Mental health conditions are diagnosable mental illnesses or symptoms that reflect disturbance in emotional, behavioral, or information processing regulation that causes significant suffering or impairment for affected individuals. These conditions have observable clinical courses and outcomes. The major costs of these conditions are borne by the individuals and their families, employers, and society. These conditions result in the disability, pain, and suffering that also accompany other serious chronic health conditions (e.g., asthma, diabetes, and hypertension).

Mental illness interventions are treatments and service delivery programs, and, in some instances, public policies designed to reduce the pain and suffering, disability, and costs of mental illnesses or to improve the delivery of mental illness care. Interventions occur in the broad context of the affected individual’s life, whether in the work, school, family, or community setting.1

The products of research-new techniques and diagnostic tools and the promise of new treatments-are inherently exciting and important to researchers and research administrators. As stated above, the act of generating new knowledge is not an end in itself, however. Ultimately, the knowledge must lead to improved public mental health in measurable and meaningful ways.

This chapter reviews various issues that must be addressed to enhance the social and public health value and impact of NIMH’s efficacy, effectiveness, practice, and service systems research. It offers three specific infrastructure goals intended to make NIMH-supported research more relevant to the needs of diverse individuals and organizations-stakeholders in the research enterprise:

Prioritize: NIMH should create a planning process for intervention research that integrates public comment from all key perspectives (e.g., patients/consumers, family members, clinicians, purchasers, policymakers, insurers, and researchers) in setting priorities for research.

Identify: NIMH should renew its role in providing a forum for focusing the key perspectives in the research enterprise through its convening power.

Monitor: NIMH should collaborate with other Federal agencies to establish an infrastructure to monitor public mental health and study the impact of research and policy changes on it.

These activities are highly interrelated. The success of the planning process will be contingent on the extent to which it incorporates stakeholders’ perspectives and leads to research that positively affects the status of mental health and quality of care. The public mental health status must be tracked to understand what has been accomplished and what remains to be done. The planning process should blend an understanding of public health need with awareness of scientific opportunities that will increase both the efficiency and value of NIMH’s research investment.

Key Perspectives and Priority Setting

There are many contributors to and patients/consumers of research on mental illness. Although the diversity of opinions within these groups cannot be fully captured in a brief paragraph or two, identification of these groups and their general issues are mandatory for understanding the breadth and complexity of this arena.

Individuals with Mental Illnesses and Their Families

Individuals with mental illnesses2 and their families have asserted themselves as active participants in developing treatment and rehabilitation plans with their care providers. Grassroots groups such as the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, the National Mental Health Association, and the National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association have formed a concerted effort to eliminate stigma against mental illness, promote access to care, foster self-help, advocate for research targeted toward the elimination of mental illnesses, enhance the utility of research from a patient/consumer perspective, and influence policymakers. Policy targets include fostering research/treatment/services advances and enacting anti-discrimination laws. Such groups have wielded considerable influence on policymakers by providing accounts of the devastation of mental illness, as well as personal gains and triumphs achieved through research advances.

These individuals want to be active participants in the priority-setting process to enhance the effectiveness and availability of treatments. They seek out, for example, research on viable treatments that both provide symptom relief and improve their functional status. They believe that better treatments with fewer side effects can be developed.

Clinicians

Clinicians are the individuals who directly provide treatment or services to individuals. These may be specialists in mental health care or primary care doctors and nurses. From a clinician’s perspective, there is a concern that many treatment guidelines and procedures issued by the government, professional groups, or health care organizations may not be in agreement with each other and may not be optimal for the individuals they serve. Further, there is substantial uncertainty about the degree to which the evidence base of many guidelines relates to the kinds of patients/consumers treated by community providers. Often only suggestive rather than definitive evidence exists to inform some of the most important clinical decisions arising in daily practice (e.g., what to recommend should the initial treatment fail). Clinicians need treatments that have utility and feasibility in a variety of practice settings given available resources. They have adequate information, training, and support to use the most appropriate treatments most efficiently.

Providers also are concerned with patient/consumer receptivity to mental illness treatments and-especially in primary care settings-availability, access to, and quality of specialty providers. Such conflicts and considerations often create tensions among the goals of high quality care, compliance by providers with contracts and cost- containment goals, autonomy by providers and individuals with mental illnesses in clinical decision making, and compliance with review standards and patient/consumer preferences. In sum, developing standards of care that apply across provider groups and for a range of mental health conditions is challenging.

Purchasers

Treatment of mental illnesses takes place in a two-tiered system (employer and commercially paid insurance, or public system). This complicated system impacts both the continuity and quality of care, as well as to what degree scientifically based knowledge is applied. The continuum of settings for treatment of mental illnesses extends from primary to specialty care and from private to public systems. Within each segment, there are additional discrete subsystems for children and adolescents, the elderly, those with serious and disabling mental illnesses, and other patient/consumer groups. Moreover, patterns of care change frequently as a function of managed care, public sector reforms, availability of new medications, and other scientific, economic, political, and social factors.

Employers and public agencies (i.e., local, State, and Federal programs) often are referred to as purchasers. They finance the services and exercise choices over benefits offered to eligible providers or service locations, and sometimes regulate prices of mental health services.

Employers. Private employers are looking increasingly at both the direct (treatment) and indirect (e.g., lack of productivity while on the job or days missed from work) costs of health care. A major concern of employers is whether employees return to work in a timely way and are productive. All employers, large and small, public and private, cannot survive with mounting medical insurance costs, employee absenteeism, or workers incapacitated by mental or general medical illness.

Additional needs identified by private sector employers include: (1) better health system performance measures to assess the quality of care and the impact of treatment on the individuals functioning; (2) an ongoing and collaborative exchange between employers and health care researchers; (3) the conduct of population-based services research in the public sector; (4) information on comorbid conditions (e.g., 60% of children with serious mental illness have a co-occurring condition within 3 to 5 years); (5) issuance of local or national treatment/performance guidelines to assist in writing specifications for benefit components; and (6) service systems research on organized systems of care, costs of treatment in offsetting other costs such as medical visits, disability, recurrence, etc.

Public Purchasers. During the past several decades, the public mental health system has changed dramatically. Changes initiated via the 1963 Community Mental Health Centers Act (Title II, Public Law 88-164) stimulated creation of new community mental health organizations. The combination of new treatments and civil rights-related reforms led to the policy of deinstitutionalization.

The early years of deinstitutionalization largely involved hospital downsizing, without adequate creation of community care alternatives. Stimulated by the 1977 Government Accounting Office (GAO) audit of deinstitutionalization (U.S. GAO 1977), the report of the President’s Commission on Mental Health (1978), and the Community Support Program initiated by the NIMH (Turner and TenHoor 1978), States made dramatic changes in public mental health programs in the last 15 years.

The number of inpatient residents at year end in State and county mental hospitals has dropped dramatically from approximately 370,000 in 1969 to about 83,000 in 1992 (Redick et al. 1996). Similarly, the number of inpatient beds in State and county mental hospitals decreased significantly from approximately 413,000 in 1970 to about 93,000 in 1992. In 1993, for the first time, State mental health agencies’ expenditures for community programs exceeded spending on State psychiatric hospital inpatient services (National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, Inc. 1996). The expansion of Medicaid to cover “optional” clinic and rehabilitation services helped to stimulate this significant redistribution.

As the publicly funded mental health system continues to evolve, policymakers in State and local mental health need more access to research results and evaluation methodologies. Key questions for public purchasers include: (1) how to incorporate or promote the use of research-based treatments and treatment guidelines and quality improvement processes in decentralized community care systems; (2) how to control cost increases (e.g., in Medicaid) without incurring the worst consequences of badly managed care; (3) how to promote concepts of recovery; (4) how best to engage and impact on mental health care in schools, prisons, and other non-mental health settings; and (5) how to improve the quality of care for the very significant percentage of patients/consumers with co-occurring illnesses.

Insurers and MCOs

Insurers and MCOs either serve as intermediaries between purchasers, providers, and patients/consumers, or they organize and deliver services. Insurers and managed care companies are subject to legislative and court-ordered regulations, as well as market demands for services delivery. Issues of particular contemporary concern include understanding the ways payment systems impact access and the quality of care delivered.

Particular interests of MCOs concern balancing cost and quality implications of treatment and service delivery programs and ensuring that populations served in managed care (or covered through insurance) are represented adequately in intervention. Studies of the effect of markets on delivery of mental health services in the public and private sectors and research that tracks changes in market factors that potentially may affect care also provide needed policy-relevant information.

Effectively engaging the managed care industry in a research agenda, which will require addressing proprietary concerns regarding data systems and management mechanisms, is as important as it is challenging given MCOs’ growing presence in the service system. Common ground may be found in the evaluation activities regarding the impact of treatment programs and policies, such as utilization review, that influence the probability of successful/effective treatment.

Policymakers

Policymakers formulate or interpret the rules, regulations, or laws that affect public health. In this context, mental health often competes for resources with other types of health problems and, at times, with housing, education, social programs, defense programs, etc., particularly at State and Federal levels. Court interpretation of legislation and resolution of conflicts (e.g., suits) is another policymaking forum that affects the availability and delivery of mental health interventions.

Policymakers are concerned that the data on treatment and services all too often are not relevant to the constituent population or are not provided in a timely manner. Policymaking occurs in real time. Research findings may lag considerably behind policy decisions they were initially designed to inform. Thus, it is important both to increase the relevance and timeliness of research endeavors to policy issues and to initiate a process of identifying and evaluating trends in public policy as they are forming.

Information on cost-effectiveness of mental health interventions is needed to formulate a rational mental health benefit plan. Most policy debates are informed by available data on cost implications, but information on the likely impact on public mental health also is needed. However, outcome data are more likely to be available at the efficacy level, rather than at levels that address policy decision issues.

Researchers

Researchers conduct studies designed to answer questions posed by the various constituents. They are concerned with ensuring that their studies provide valid answers to the concerns raised by these groups. To do so, they must be able to formulate questions into a theoretical model that can be studied. Without an existing base of knowledge in a particular area, it may be difficult to develop such models. In addition, researchers must be clear about what to measure so they can answer a question. Even more importantly, they must have measures that are reliable and valid.

Many researchers operate in academic settings and must compete for private or Federal grants to support their research efforts. They also strive to publish their findings in a timely manner. Large, complex studies also can be difficult to conduct within one academic setting. Seeking out new collaborators in other locations can be costly and difficult. Due to these constraints, researchers sometimes must simplify their research questions. Thus, many investigators believe that the funding incentives have been weighted toward conducting more simplistic studies that may not generalize well to larger populations of individuals seeking treatment or services.

Figure 5 reflects the larger context in which these key stakeholders operate. These components and their interconnections are where science and mental health policy converge to shape better care and service for individuals with mental illnesses.

Figure 5: The Context of Public Mental Health

Issue: Integrating Public Health Benefit and Scientific Merit to Establish a Research Agenda

Even though one can define science in value-free ways (e.g., theory building and testing based on replicable results), values are clearly felt in the arena of research. Values determine which research idea, out of the many presented to NIMH, receives taxpayer support. Yet, if the research agenda were to reflect predominantly the needs of only one of the many stakeholders, it would be unbalanced and much could be lost.

Research that may be of great benefit to individuals with mental illnesses may be less compelling to researchers. For instance, a fairly simple treatment comparison trial may have high impact on developing evidence-based practice. Comparison studies clarify which treatment a patient/consumer should try next or inform a State mental health commissioner about whether to adopt a new treatment guideline. If the researchers alone were setting the agenda, however, these trials might be insufficiently valued to recommend funding.

As another example, NIMH must develop channels for input from policymakers regarding the biggest decisions they are facing. For example, as State mental health authorities must decide how to allocate their fixed treatment dollars, the NIMH research portfolio should help inform their decision making about which services should be provided, to whom, by whom, for how long, and how to implement such changes in practice. Similarly, health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and other managed care entities should be able to look to NIMH for research findings on how best to treat those conditions that are most common in the people they serve and how to know whether such care is being delivered. Providing timely, useful information to these purchasers and policymakers should also enhance their participation as research partners. Dr. Steven Shon explains the issues from a policy perspective (see story box).

Research and Policy Decisions: Obstacles to Effective Translation

As someone in a public policy position, connecting research to practice and policy decisions is often extremely difficult. The difficulties for me occur in the following areas:

1. Obtaining knowledge about relevant research

As each year goes by the volume of published research and descriptive articles increases. Sifting through these publications in order to find research findings that may be relevant to public practice is time consuming and difficult. There is no single arena or source of information which can synthesize the most important or relevant findings.

2. Lag time between research findings and publications

Important research findings may take years before they are available in published form. This lag time may result in missed windows of opportunity for public policy decisions.

3. Focus of research in relation to public policy

Most clinical research does not address the most relevant public policy considerations that would be useful for mental health. Useful research available to public policy people is woefully lacking. The focus of much, if not most, funded research is different than what most public policymakers would propose.

4. Timeliness of research in relation to public policy

In my experience, most research on important public policy issues in mental health occurs long after decisions have been made. Very seldom are there relevant research findings available to influence policy decisions. Again, this is probably due to #3.

Many of the thorny issues that mental health public policy officials are struggling with today were identified as issues on the horizon many years ago and still today there is little in the way of good research to guide decisions.

I think that the current situation could be significantly alleviated by creating a stronger and more collaborative link between mental health public policymakers and research funding entities. Through such a process, forums could be developed to help identify important future research directions, as well as design better mechanisms for updates, interpretation of data, synthesis of important research, and the dissemination of relevant research findings that have the potential for impacting public policy.

Dr. Steven Shon is the Medical Director, Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation.

The priority-setting process must involve all stakeholders (patients/consumers, providers, purchasers, and policymakers) to enhance the ability of NIMH to anticipate the types of questions on the horizon. NIMH can then project trends that influence mental health service delivery, benefits, or public mental health, and anticipate the need for relevant intervention research data. Tracking developments in public policy is necessary to anticipate informational needs and to review existing research and formulate new initiatives to fill critical gaps.

The Workgroup encourages NIMH staff to explore models at other agencies or institutes where priority setting is underway. At the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), for example, the research priority-setting process is done annually and spans three fiscal years. The process opens with a summer policy retreat designed to address research priorities and public health needs, including emerging scientific opportunities, policy issues, special problems, and consideration of refinements to previously approved initiatives. The broad-based process, which may involve invited participants from outside of the NIAID, integrates priorities for both the extramural and intramural programs. Feedback on issues raised at the summer policy retreat are submitted to the fall meeting of the NIAID Advisory Council. During the winter program review, current and future divisional priority activities are discussed. A general consensus is obtained on the prioritization of these activities. Further communication then takes place among the divisions. These findings are presented to Council and concepts are cleared for initiating program announcements (PAs), requests for applications (RFAs), and requests for proposals (RFPs). In addition, issues of interest are posted on the Institute’s web site to inform the extramural community of future priority areas and to provide an opportunity to comment.

Other institutes and agencies have planful approaches, and NIMH staff should consider these and adapt or adopt attractive elements into their priority-setting process.

Recommendation 1

NIMH should establish an ongoing priority-setting process that integrates the perspectives of patients/consumers, providers, purchasers, researchers, and policymakers in determining long-term initiatives and responding to scientific opportunities to improve the relevance of mental health intervention research.

Issue: Research-Based Consensus Development

Establishing a research agenda that is responsive to the needs and priorities of key stakeholders is likely to increase the usefulness of research results. But such agenda setting requires both a forum and information from which consensus can be achieved. Choices exercised by each of these stakeholders can affect whether treatments for illnesses are available, who receives them, and the costs and quality of care. Not surprisingly, these decisions are difficult because the research findings needed to inform a proper response are not always available. As a result, multiple parties are forced to make unenviable choices:

- Patients/consumers are uncertain as to whether they should continue to take medication to alleviate symptoms but increase risks of significant side effects. Should they pay out-of-pocket for new medication(s) with reportedly fewer side effects or continue with the less expensive but more troublesome drug(s) offered through providers or MCOs? What forms of psychotherapy will help? Would their time be better spent in a supported employment program?

- Providers seek to give high-quality care to individual patients/consumers, but also must comply with various insurer requirements for cost-cutting measures. How should they allocate their time?

- Employers seek to optimize employee satisfaction and productivity as well as profitability. Will more extensive coverage produce better care? Will treatment help productivity?

- Insurers and MCOs must compete for a better market share and for contracts, without sacrificing patient/consumer satisfaction. Will paying for prevention or health activities have short-term payoffs or simply minimize cost for the next insurer?

Given the often conflicting goals within and across stakeholder groups, the field would benefit from having a forum to identify, develop, and chart a shared path to achieve shared goals. Over the last 9 months, the Workgroup began to develop such a forum by devoting significant time to hearing from representatives of these diverse sectors.

The Workgroup urges NIMH to play an active role in establishing, maintaining, and using this critical forum. As an overarching principle, coordination and cooperation with all of the Federal agencies addressing mental health and substance abuse problems are encouraged. The Institute should review past, successful use of its “convening power.” A recent example was that of an NIMH-sponsored meeting of all parties concerned with the lack of research to direct pharmaceutical treatment in children, an urgent and important issue in light of the large number of off-label prescriptions written for children in this Nation (Vitiello and Jensen 1997). Drs. Peter Jensen and Benedetto Vitiello, both of the NIMH, invited representatives from parent groups, the pharmaceutical industry, ethicists, researchers, and clinicians to focus on this issue and define what was needed and what they could contribute to this effort.

The Workgroup encourages the NIMH to participate more actively in other institution’s consensus efforts. The NIMH has had a liaison member on the National Advisory Council for the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) since its inception, yet the CMHS Council has expressed concern that closer ties need to be created. The need for collaboration is particularly clear given overlapping responsibilities in public information and evaluation of effective interventions. The Workgroup shared this sentiment and extends it to private foundations and businesses.

Recommendation 2

NIMH should renew its role in providing a forum for focusing the key perspectives in the mental health research enterprise to develop clear and productive lines of bi-directional communication.

Bringing people together is not sufficient by itself. Each group requires easily accessible syntheses of research findings to inform their positions. These syntheses should not be limited to NIMH-supported research. Although the NIMH plays a unique role in sponsoring public research on mental health care delivery and treatments, other governmental agencies [e.g., Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) and CMHS], several large private foundations, pharmaceutical companies, and health care delivery systems, such as large HMOs, sponsor research that has overlapping goals.

The Internet is emerging as a primary source for organizing and manipulating information quickly. With this capacity, the challenge for the mental health field is to synthesize research findings and present them in a way that researchers and other important groups can evaluate the information. The work of the Cochrane Collaboration, an international group established to conduct systematic reviews of the literature, offers an example of how large amounts of research data are being collected and managed. It also provides an historical context to determine if the conduct of a future study would be duplicative. Other synthesis processes exist as well, and can be brought to bear on the Institute’s scientific priorities.

Recommendation 3

NIMH should support the synthesis of available information on mental illnesses, their treatment, and service needs to enhance priority-setting meetings.

Just as NIMH must renew its efforts to synthesize information, it also must take the lead in consensus development. Consensus development conferences are effective in bringing together all stakeholders; thus, as findings emerge from research and large-scale synthesis efforts, NIMH, in collaboration with other Federal agencies such as AHCPR and CMHS, should actively initiate such conferences. The results of these conferences would then shape NIMH’s priorities and be of guidance to the large purchasers of care such as State mental heath administrations and MCOs.

Recommendation 4

NIMH should routinely organize consensus development conferences on specific mental illnesses to synthesize the research findings.

Recommendation 5

NIMH should conduct these activities in conjunction with appropriate partners, such as CMHS and AHCPR, to provide the necessary integration for the Federal effort.

Issue: Creating an Infrastructure for Monitoring Public Mental Health and Assessing the Impact of Research

Mental illnesses exact a tremendous toll on society as a whole. Public systems must reallocate increasingly tighter resources and are being forced to make very difficult decisions regarding what services to provide. Private purchasers are concerned about not only the costs of paying for mental health benefits, but also the costs of lost productivity associated with illness.

As sweeping changes in health care unfold, researchers and policymakers want to examine the effects of these changes on the public’s mental health status. An enduring problem in assessing the value of a mental health intervention is that there is no general index of the Nation’s mental health status. Although short-term epidemiological studies have provided critically important “snapshots” of the country’s mental health status, it is difficult to ascertain whether the Nation’s mental health has improved, since studies tend to be conducted too far apart in time and with sufficiently different

methodologies to allow evaluation of change. Similarly, national health surveys have periodically included mental health items, but not in a consistent manner to allow this level of monitoring.

Lacking an index, it is not possible to assess fully the large-scale changes in the mental health status of a State or the Nation. Each study that addresses this question must do so in a vacuum. At present, the only method to assess changes is to compare results of the few studies conducted at restricted points in time. Measures of mental health status used in these studies must be created or adapted for that specific project, and staff must be trained to implement these measures. Such costly, intensive efforts are prohibitive for an individual researcher, the State, or even a single institution such as NIMH. For this reason, developing methodologies that can be included or incorporated into ongoing surveys in a routinized manner is essential. Similarly, sampling methods have not been used effectively in assessing the patterns or needs for mental health services.

Improvements in public mental health are contingent on improvements in access to care and services delivery. Thus, it is important to measure the status of the care delivered in actual practice so decisions about improving the quality of care can be made. This is potentially a more demanding monitoring task, because quality of care may require studying providers and service delivery systems, not just representative individuals in the household or patients/consumers of care and services.

No national databases of the diverse spectrum of mental health providers or service systems exist to enable either national monitoring efforts or individual studies. Similarly, there are no national lists of health care delivery systems. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration regularly surveys larger public mental health providers through its inventory of mental health care organizations, but individual providers, MCOs, and social rehabilitation agencies are not included. Without augmenting the current infrastructure to tap into representative providers or mental health care systems, it is prohibitively expensive for individual studies to improve their sampling at higher levels (systems, providers). Current efforts will be limited and less representative over time, as is already reflected in the empirical literature by a disproportion of case studies.

A limited number of intensive, short-term studies of the Nation’s mental health status assessed continuously over time offer an alternative infrastructure for measures of progress, change, and value. Indicators of particular interest should be those that are potentially changeable through treatment interventions. In addition, researchers conducting local or regional studies could incorporate these indicators, thereby testing their findings against the Nation at-large. As a research agency, NIMH should “define the gold standard” for what should and practicably can be monitored (i.e., establish a process to determine the priority areas).

At the national level, for example, it would be useful to ascertain the number of patients/consumers with particular diagnoses who are and are not receiving treatment, where treatment is being provided, and the nature of treatment received. At the local level, an example is seen in the provision by school districts of information about the percentage of children who require special education services and the percentage evaluated by guidance counselors or other mental health professionals within the school setting.

NIMH should provide leadership in developing the infrastructure to regularly and reliably track mental illnesses and the impact of treatment breakthroughs or policy changes in the organization or financing of systems of care on public mental health. A secondary goal of this monitoring is the provision of the next generation of research findings to inform the priority-setting process. Key activities would include coordination with current Federal efforts to develop an economical, written plan for presentation to the NAMHC. It is difficult to think of such a complex project and use the term “economical.” Nonetheless, embedding the NIMH effort into ongoing studies, effectively using sampling strategies, and collaborating with highly experienced Federal agencies should permit a relatively low-cost effort. This is especially feasible given the expected payoff in the type of information policymakers need and patients/consumers want, as well as stimulating more public health relevant research. Specific recommendations on the methods development required for this effort are presented in Chapter 4.

Recommendation 6

NIMH should collaborate with Federal, State, and private agencies to establish a mechanism to monitor the value (as defined by an equation of quality, access, and cost) of mental health care delivered across the Nation and the impact of policies on practice and service systems.

Summary

NIMH should develop a process that integrates the input of diverse stakeholders regarding research priorities, data from systematic monitoring of public mental health and quality of care, and information derived from research funded by NIMH and other organizations. Each recommendation in this chapter represents one step toward development of an informed priority-setting process for the research agenda. Priority-setting based on public mental health values and real impact data will raise the Institute’s research portfolio to a higher level of scientific and public health excellence. This effort is devoted to meeting the primary goal of research supported by NIMH: improving the condition of people with mental illnesses.

Chapter 3

Making Connections

Introduction

Scientific research has generated information that has enhanced greatly the lives of many individuals with mental illnesses. By way of example, recent developments that carry immense potential for improved clinical care are:

- A virtual explosion in the availability of sophisticated new treatments – Nine new antidepressant agents have become available in the U.S. since 1988; three new atypical antipsychotic agents have been introduced within the last 5 years; and at least three compounds (clozapine, lamotrigine, and gabapentin) currently are being studied for efficacy in bipolar disorder;

- A shift from the primacy of “expert opinion” to that of scientific evidence as the basis for treatment decisions – As mental illness diagnoses have been refined and shown to be as reliable as those used in general medicine (Spitzer, Forman, and Nee 1979; Williams et al. 1992) and as treatment options have multiplied, evidence-based treatment guidelines, specific disease management protocols, and medication algorithms are being formulated and tested (Depression Guideline Panel 1993; Frances et al. 1998; International Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project Participants 1995);

- Numerous research findings on innovative delivery system configurations – For example, findings on the effectiveness of Assertive Community Treatment teams can inform policies as to preferred methods of delivering care for persons with severe mental illnesses (p. 580).3